Namadicus: Last of the Elephant Kings

You stand at the edge of a tight broadleaf grove beneath a cathedral of stars, the snowy ground faintly illuminated by the glowing axle of the galaxy. The dark wind is raw and cold, howling through the pine needles. Biting into your rosy face. Chilling your bones. You huddle against a ghostly dogwood. Its bare branches flailing wildly in the night like vantablack bolts, bansheelike, invisible except for the occasional, momentary snuffing of a star by one of the tangent twigs.

Under the silent watch of Thuban, the pole star, you gaze out into the clearing, watching swirls of snow dance in the bitter wind. You’re suddenly aware of something moving through the dense forest on the other side of the field. Something big. You can’t feel the ground trembling beneath its feet. No tree trunks cracking in the distance. No ripples of water in a cup to alert you to its presence. You just know it is out there, as though its mere proximity allows you to be aware of it.

The creature strides out into the clearing, not disturbing a single barren branch despite its imposing size. It’s too huge to have ever worried about predators, so it takes its time. Its snow-muffled steps are calm and dignified, each one telling you that this is the king of the forest. It stops and shakes a dusting of snow off its back before continuing towards you.

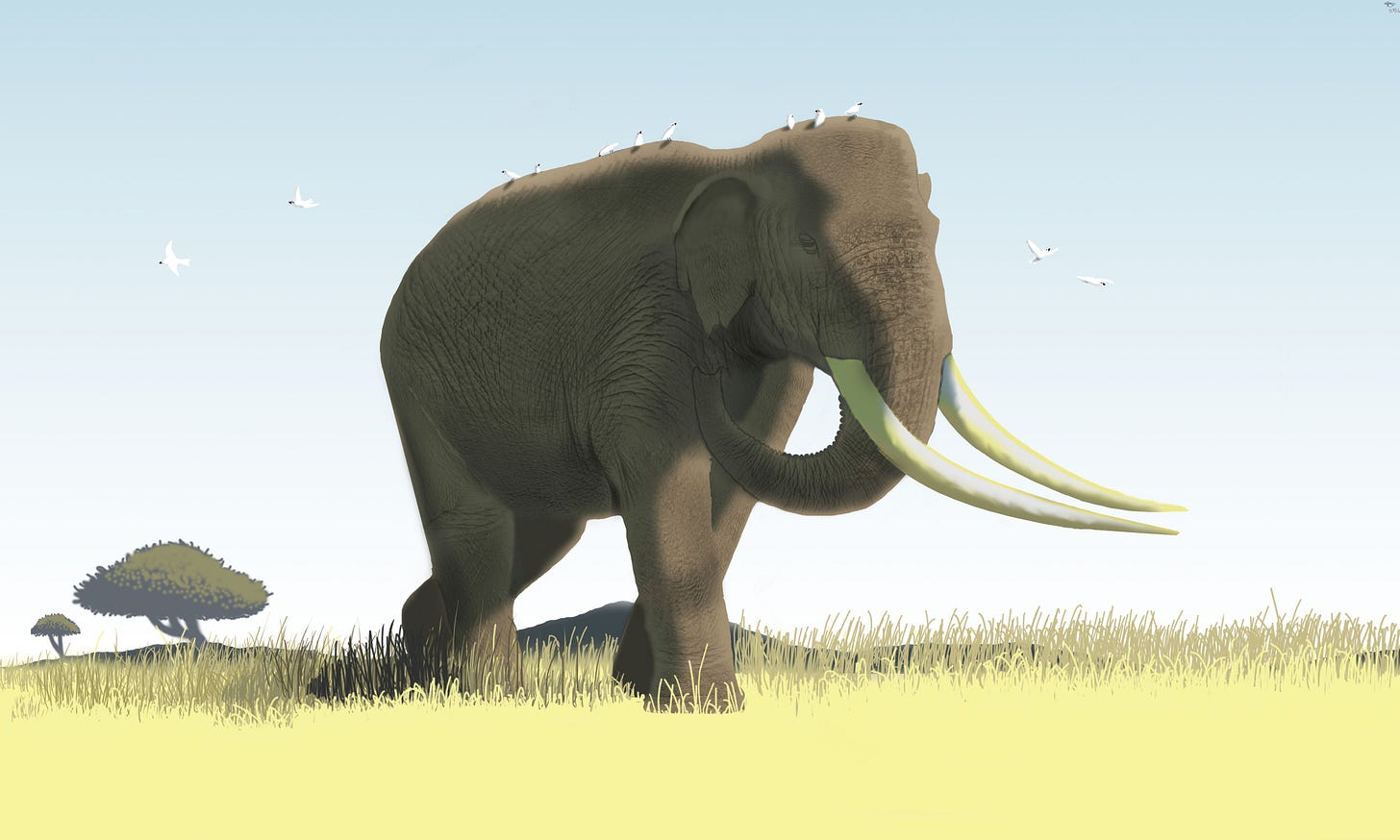

It’s an elephant. A kind you’ve never seen before, far too massive to be the familiar African or Asian varieties. You guess it’s about seventeen feet at the shoulder. Its head crowned by a huge, double-humped crest that slopes down into a commanding brow-ridge. Tusks jutting out like cutlasses, broad and warlike, gleaming pale against the sable hide. When it finally notices you and raises its colossal head, its trunk stretches higher than any tree in the forest, exhaling steam like a smokestack. The bellowing trumpet reverberates through your body, vibrating every bone like a tuning fork, demanding your undivided attention as a flourish of buisines announces the arrival of a monarch.

You’ve just met Palaeoloxodon namadicus, the largest land mammal to ever live.

In The Hall Of The Elephant King

Big. If there is one word suited to describe Palaeoloxodon namadicus, it’s big. Not mammoth. Mastodonic doesn’t work either- P. namadicus dwarfed them both. At 22 tons, P. namadicus weighed more than three woolly mammoth bulls combined. Nearly double the weight of the largest African elephant on record- an Angolan bull that clocked in at 12 tons.

P. namadicus is only known from partial remains, so much of its anatomy remains shrouded in mystery. Nevertheless, we know that its bones were much thicker and stronger than those of modern elephants, necessary to support its immense weight. Mass estimates for P. namadicus have largely been obtained by volumetric analysis of fossil limb bones, mostly femurs- shoulder height is calculated based on limb lengths using living elephants as a baseline, and from there body mass can be estimated- and some of these femurs are truly gigantic. An 1834 find in Sagauni yielded a femur measuring 1600mm, suggesting a weight of 13 tons. This bone wasn’t fully fused, so it probably belonged to an adolescent that would’ve grown considerably larger if it had lived longer. In 2006, a P. namadicus femur was found in the Narmada River in India that measured 1490cm in length; the animal to which it belonged would have stood around 4 meters at the shoulder. Another partial skeleton found in the Godavari River had an estimated shoulder height of 4.5 meters.

Other even larger specimens were discovered in the 1800s and early 1900s. Another specimen found in Sagauni would have stood 5.2 meters at the shoulder and weighed over 22 tons. This individual would have outweighed many sauropod dinosaurs, being roughly the same weight as Apatosaurus louisae, double the mass of Diplodocus carnegii, and three times the weight of Saltasaurus loricatus. It also handily outweighed many other famous dinosaurs like Stegosaurus stenops, Triceratops horridus, and Tyrannosaurus rex.

For a long time, it was believed that Paraceratherium- an extinct species of rhinoceros that lived 23 million years before Palaeoloxodon- was the largest land mammal of all time. The largest known specimen is estimated to have weighed around 17 tons, which is still impressively large, but the 22 ton P. namadicus has taken its crown fair and square. It’s still up in the air whether or not Paraceratherium would have been taller than P. namadicus, though. While P. namadicus was 40cm taller at the shoulders, Paraceratherium’s long, giraffe-like neck may have been able to hold its head above any Palaeoloxodon.

Paleontologists don’t actually know the true upper size parameters of P. namadicus. We have a decent grasp on the average, but every so often a giant individual of a species is born that is much larger than average or even a typical larger-than-average specimen. For example, the average female blue whale weighs around 123 tons, but the record-holder weighed over 219 tons. Putting it taxonomically closer to P. namadicus, African elephant bulls average about 5.5 tons, but the record is more than double this. Such enormous individuals are not common, numbering only one in thousands or millions, so it’s unlikely we’ll ever find a real giant Palaeoloxodon, but there were in all probability some truly colossal elephants roaming Eurasia.

Emphasis on the size of the animal isn’t just to impress the reader- knowing the mass of an animal is crucial if you want to know how much food and water it needed to sustain itself, how fast it could move, its population density, its brain-to-body-ratio, its probable average lifespan, and many other characteristics. You can’t reliably estimate these things if you don’t have some clue as to the animal’s mass.

As might be expected for such a big animal, P. namadicus was immensely strong, making it the most powerful elephant to ever live. Its legs were more heavily built than those of extant elephants, with thicker and longer bones to handle the increased stresses of locomotion at that size. Perhaps not surprisingly, Palaeoloxodon couldn’t run, but because of its long stride it still would’ve been able to cover a lot of ground daily. Modern African and Asian elephants can’t run either- running being defined as having a suspended phase in the stride where all four limbs are off the ground- but they can still move fairly quickly. You certainly wouldn’t want to be chased by a bull Palaeoloxodon in musth.

Palaeoloxodon was also by far the broadest of any proboscidean. Between it, mammoths, mastodons, gompotheres, deinotheres, and extant elephants, it’s not even a contest. They also possessed the largest head of any proboscidean to ever live, their skulls measuring 4.5 feet from the skull roof down to the base of the tusk-sheaths.

Skull musculature in Palaeoloxodon is well studied. Both modern genera of elephants- Loxodonta (the two species of African elephants) and Elephas (the Asian elephant)- possess the splenius muscle, which anchors to the occipital ridge and stretches back over the posterior cranium (the back of the head), helping with head movements like shaking. In Elephas, there is an additional muscle lining the splenius called the splenius superficialis, which provides additional strength to support the massive head and tusks; it also gives a distinctly double-domed appearance to the Asian elephant head. In Palaeoloxodon, the parieto-occipital crest is massive, suggesting that it had this muscle and that its head and neck were much stronger than those of extant elephants. This has implications for the animal’s behavior- intraspecific combat between Palaeoloxodon bulls must have been a fierce and magnificent spectacle.

Since elephants have columnar forelimbs, the trunk of P. namadicus must have been quite long. An elephant’s trunk has to be long enough to reach the ground without bending its legs, otherwise it can’t drink. The tusks likewise were very long, sometimes almost as long as the animal was tall. Palaeoloxodon is sometimes called the “straight-tusked elephant” but this is a bit of a misnomer, as the tusks have a slight upward curve to them, more like cutlasses than broadswords. They are far straighter than the tusks of mammoths or extant elephants, though. From the front, the tusks of Palaeoloxodon would have almost looked like open arms.

Ear size in Palaeoloxodon is impossible to estimate, but it can be inferred from the warm forest climate they lived in that their ears were large to help with shed excess body heat, just like modern elephants, though whether or not their ears were more like those of the African or Asian elephant is entirely up to speculation. Meanwhile, the ancestor of P. namadicus, P. recki, probably had ears similar in size to the African elephants with which it coexisted, so it could dissipate heat more effectively. Related to heat regulation, they probably weren’t furry. They didn’t live on extremely cold steppes like the woolly mammoth, so a lot of fur on an animal that size would have been detrimental to homeostasis, since they were more than capable of retaining their own body heat.

It’s important to note that Palaeoloxodon wasn’t an inscrutable antediluvian beast. It was very similar to modern elephants. They lived mainly in humid forests, subsisting on a mixed diet of leaves, shrubs, fruit, bark, and grasses. Their predominantly browsing lifestyle may be the reason they were so tall, to better reach the canopies. A Palaeoloxodon rearing on its hind legs, which they were certainly capable of, would have been able to clear the top of almost any tree in Europe. Straight-tusked elephants may have seasonally migrated between forests and savannas during the wet season, when the grass grows faster. A wet season migration would also have allowed calves to grow quicker, with plenty of water gathered up in ponds and the fresh grass providing nutrition for females and, by extension, their breastfeeding calves.

Based on a rare and exquisitely preserved fossil trackway, the straight-tusked elephant lived in matriarchal herds, just like modern elephants. The behavior of males is a bit of a mystery. They may have been solitary like the African forest elephant, or they may have formed friendships with other males and lived in small groups. The trackway evidence supports the idea that older males, at least, were solitary. Males would also have been much larger than females- bone data from Palaeoloxodon antiquus, the better-known European cousin of P. namadicus, suggests that while males continued growing into their fifties, the female growth curve flattened just after puberty, usually about 11-14 years old in extant elephants. P. antiquus females plateaued at around 5.5 tons, meaning males were over double their mass- P. namadicus females would have been heavier, but still laughably small next to the males. The size difference is because land mammals have a definite upper-size limit, where gestation just becomes too long. Modern elephant pregnancies last about two years, so the gestation time of Palaeoloxodon had to have been at least this long, and was likely a good deal longer.

They had very long lives. Elephants are the longest-lived terrestrial mammals besides humans, with African and Asian elephants both averaging about 60 years in the wild. Given their larger size, it has been conservatively estimated that the various species of straight-tusked elephant may have lived to be between 68 and 70, but due to uncertainty about the genus’s growth rate- some bones didn’t fully fuse until the animals were near 50- an average lifespan of 80 has also been proposed. Again though, there are always some individuals in a species that reach an exceptionally old age- there are octogenarian Asian elephants- and Palaeoloxodon was likely no different. It’s possible that at one point in time, there was a centenarian elephant lumbering through a Eurasian forest.

A Proud Bloodline

The origins of the Palaeoloxodon genus are a bit of a mystery. It first appears in the fossil record in Pliocene Africa, 3.5 million years ago, as the titanic and fully-formed Palaeoloxodon recki. P. recki is estimated to have weighed upwards of 15 tons and stood 4.27 meters at the shoulder. It was the dominant species of elephant in Africa during the Pliocene and for most of the Pleistocene, going extinct around 130,000 years ago during a severe drought period. After its extinction, it was replaced by Loxodonta africana- the modern African bush elephant- as the dominant elephant on the continent.

But before it went extinct, it had migrated out into Eurasia, diversifying into several different species. Palaeoloxodon antiquus inhabited western Eurasia, ranging from England all the way to Kazakhstan between 780,000 and 28,000 years ago. When they first arrived in Eurasia, the continent was already populated by elephants- the famed woolly mammoth, and several other species of mammoth that had lived in Eurasia for over two million years. Their diet helps explain why the species were able to coexist- while the straight-tusked elephant was a forest browser, mammoths were primarily grazers on the icy steppes.

P. antiquus was also quite large, though somewhat smaller than P. recki, averaging “only” around 13 tons and 4.2 meters at the shoulders. While mostly going extinct around 115,000 years ago at the onset of the Last Glacial Period, it survived in Iberia until around 28,000 years ago. P. namadicus is sometimes considered a subspecies of P. antiquus, but the immense size differences and differences in skull morphology between the two populations don’t support this notion- P. antiquus’s skull crest was nowhere near as pronounced as on P. namadicus.

There is some evidence of hunting by hominins, with multiple P. antiquus bones showing signs of butchering by early humans and/or neanderthals, but it’s more likely the animals had already died and were being scavenged, rather than having been killed by hominin hunters. Most of the animals that were definitively killed by hunters were calves, suggesting that elephant calves were an important part of the early hominin diet, including Neanderthals. Vulnerable females in delivery and stillborn calves were also likely eaten by Neanderthals. Many of the sites date back to 300,000-400,000 years ago, and even P. antiquus’s Iberian redoubt ceased to be long before the end-Pleistocene “blitzkrieg” of extinctions, so overkill was not a component to Palaeoloxodon’s extinction. Indeed, the straight-tusked elephant was probably the most dangerous animal faced by early humans in their trek across the globe. Due to its immense size it would have been extremely hazardous to attempt to take one down, and humans with a self-preservative lean may have actively avoided hunting adult Palaeoloxodon.

[CORRECTION: Tristan Rapp, co-founder of The Extinctions, alerted me to some factual errors about P. antiquus. Firstly, its extinction was closer to 50,000-40,000 years ago, rather than 115,000. It rapidly went extinct alongside other temperate-zone megafauna in Europe, and the extinction coincides neatly with human arrival on the continent. P. antiquus had also survived more severe glaciations in the past, and had been living in LGP conditions for more than 50,000 years until humans arrived. Basically, human overkill did contribute to their extinction. My own addition to this would be that, given P. antiquus’s formidable size, human hunters may have been unsustainably killing calves, rather than adult individuals- although the latter certainly occurred from time to time as well.]

Instead, it seems probable that the severe climate change of the LGP led to it being extirpated from most of its former range, with a few holdout populations relegated to southwestern Europe. Throughout the duration of its time on Earth, its territory ebbed and flowed with the advance of glaciers, retreating to warmer Mediterranean climates at the onset of icy eras. Some of these Mediterranean P. antiquus wound up stranded on islands like Malta and Cyprus, where they were subjected to comical insular dwarfism- one such dwarf species, Palaeoloxodon falconeri, was 98% smaller than P. namadicus. There were also probably other species in central Eurasia that haven’t been properly described yet, or are known from too little material to diagnose.

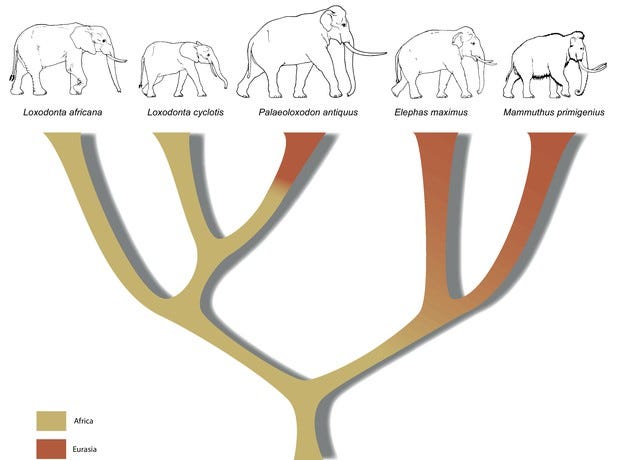

The genetics of Palaeoloxodon are curious. When the genus was first described in 1924, it was, as the name might suggest, considered to be closely related to Loxodonta. Later, morphological comparisons led paleontologists to believe it was more closely related to Elephas- understandable, given the similarities of the skull crests. However, Meyer et al (2017) upended this consensus with full-mitochondrial genome sequences of P. antiquus, which revealed the genus to be most closely related to Loxodonta after all.

The really weird part is that not only was Palaeoloxodon more closely related to Loxodonta than Elephas, but Loxodonta cyclotis- the African forest elephant- was found to be more closely related to Palaeoloxodon than it is to the African bush elephant! The two living African elephant species evolved in isolation for over 500,000 years, while- at first glance- the forest elephant and Palaeoloxodon appear to share a more recent common ancestor.

However, Palkopoulou et al (2018) complicated the picture, revealing that forest elephants don’t form a neat, simple clade with Palaeoloxodon like in the above image. Just like how prehistoric human history was rife with mixing with other hominin species- neanderthals, Denisovans, and other “ghost lineages” that we have no fossils of- there were many intermixing events between disparate elephant lineages.

Palaeoloxodon appears to have received most of its ancestry from a lineage basal to both forest and bush elephants, with two subsequent hybridization events. One of these events was with a population ancestral to woolly mammoths. It’s hypothesized that the apparent morphological similarities between Palaeoloxodon and Asian elephants, specifically the double-domed skull, could date to this time, since mammoths are closely related to Asian elephants, but it could also simply be a case of convergent evolution.

The other admixture event- the researchers were unable to determine the order in which they occurred- was with a population of modern forest elephants. If you’re lost (I was) all this means is that Palaeoloxodon shared a common ancestor with both species of extant African elephants, and then at some point later on in its evolution, it met up with more derived forest elephants and hybridized with them again, which is why it appears to be more closely related to them. It didn’t gain its genetic affinity by branching off from forest elephants directly, it took the scenic route.

Regardless of the complexities of its origin, at some point P. namadicus branched off from P. antiquus in Eurasia, perhaps during one of the glacial periods when populations in central Asia were reduced by the intense cold. Its range stretched from India to Japan, as far south as Java and as far north as Manchuria. It also spawned its own dwarf species in Japan, P. naumanni, but even this alleged dwarf still averaged around 6 tons. It lived until about 24,000 years ago, and then it too seems to have gone extinct.

Or did it?

The Last of the Elephant Kings

Wrangel Island is justly famous for being the final redoubt of the woolly mammoth. On this frigid rock, a few hundred mammoths clung to life for five millennia after their relatives on the mainland had gone extinct. Wrangel isn’t a big island- formerly part of Beringia, the mammoths had probably been stranded there during the epic floods at the end of the Younger Dryas glacial period. Here, because their population was so low, the last few hundred mammoths suffered genetic meltdown, a dramatic decline in fitness that caused their final extinction around 4,000 years ago.

Genetic meltdown isn’t pretty. A species below its minimum viable population is a stagnant pool. Bloodlines that once flowed into the pool, invigorating it with fresh genes, wither as they irreversibly drain into it. Creeks drying into muddy runnels. Soon only a bony bed remains. No new alleles. No fresh blood to weed out deleterious mutations. The pool the ark, drifting aimlessly with no hope of ever sighting land. A species can do well with second- and third-cousin marriages, for awhile. Eventually, inbreeding depression becomes so high that mating pairs are genetically the equivalent of brother and sister, or even higher. Towards the end, deleterious mutations accumulated so quickly in the Wrangel mammoths that they lost most of their sense of smell. Their coats turned a satiny, polar bear white and couldn’t retain heat as well as their ancestors’ shaggy fur. They were sickly and weak, desperately clinging to life long past the point when they should have faded into the mists of prehistory. And then, at the dawn of Khufu, they finally did.

But they weren’t the last of the great elephants.

Let’s go to China.

Today, the only elephants in China live in the southern part of the country. A scant three hundred Asian elephants confined to a narrow strip of southern Yunnan. But they used to live across a wide swathe of the region, their range stretching all the way up to the Shandong Peninsula.

They couldn’t live further north than Shandong because it’s too cold. Up in the Huabei region, there have never been any Asian elephants. But there were elephants- this is where Palaeoloxodon namadicus lived. And there’s some decent evidence suggesting they lived there very recently, up until about 3,000 years ago. This is no small thing- while the Wrangel mammoths lived in total solitude, never interacting with humans, it’s possible that P. namadicus was around at the founding of Beijing.

The bulk of the case for late-surviving P. namadicus comes from Li et al (2012). It’s a short paper and I recommend reading it. The authors present three lines of evidence- direct fossil evidence, paleoclimatic evidence, and archaeological evidence in the form of bronze elephant figures recovered from Huabei, dating to around 3000 years ago.

We’ll go through this in order from most to least convincing.

Archaeological Evidence

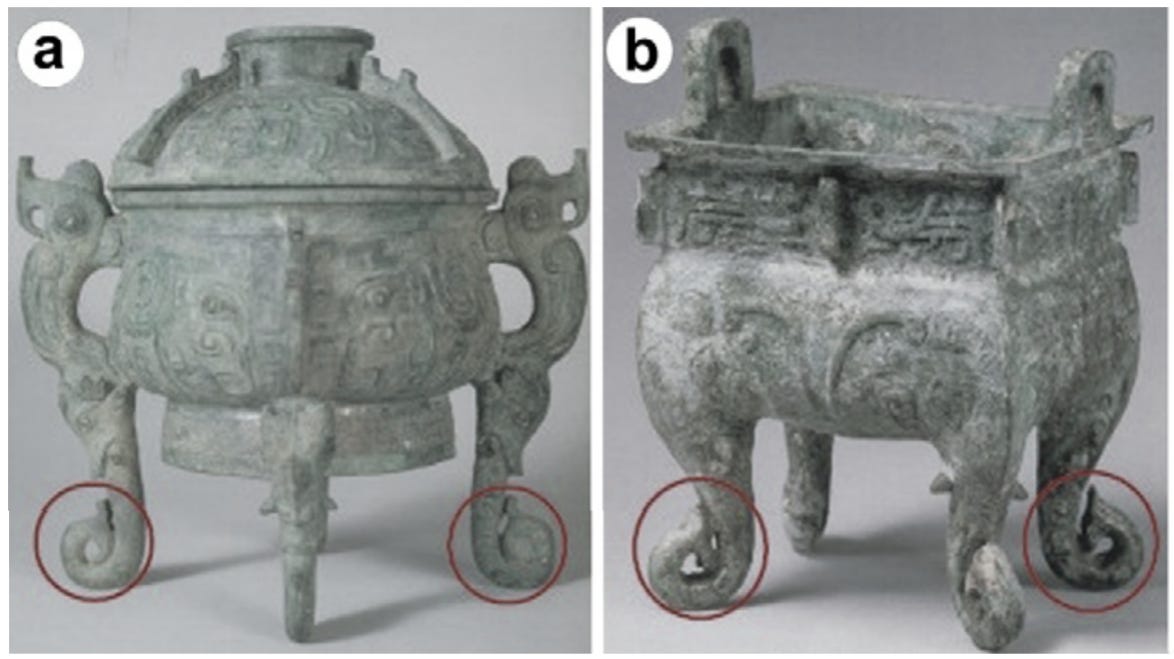

Thousands of bronzes have been unearthed from the earliest Chinese dynasties- Xia, Shang, and Zhou, ranging from about 4,100 to 2,300 years ago- including ornate elephant sculptures, dubbed “elephant zun” by Chinese archaeologists. At first glance, these appear to simply be depictions of Asian elephants, but the tips of the trunks on these bronzes suggest something else.

Before looking at the bronzes, it is important to note that there is a difference between the trunks of extant elephant genera. An elephant’s trunk is simply an extension of the upper lip and the nose, and at its tip there are “fingers” used for manipulating objects. The Asian elephant only has one finger on the tip. African elephants have two fingers, one on the top of the trunk and one at the bottom. The woolly mammoth had two fingers as well, but they were asymmetrical- the upper being finger-shaped, and the lower one flat, very different from either of the extant elephant genera. The number of fingers on Palaeoloxodon’s trunk is unknown, but given their close genetic kinship to Loxodonta, it can be inferred that they probably had two.

This is critical evidence. On the trunk of Elephas, there cannot be two fingers. But the trunks on the elephant zun always have two fingers.

With this in mind, let’s look at some of the ancient Chinese bronzes.

Further, if we go south in China to Hunan, which was indisputably the domain of Asian elephants, we can see that the “elephant zun” here have a distinctly different trunk shape, possessing the expected single-finger.

This evidence, while substantial, was roundly criticized back in 2012 when the Li paper was first published. Back then, the general consensus was that Palaeoloxodon was closer to Elephas than Loxodonta, so the two-fingered trunks were assumed to have been a mere error of stylization, or the result of some far-fetched contact between the Shang Dynasty and Africa. But, as we’ve seen, DNA shows that Palaeoloxodon was in fact a phylogenetic sibling to Loxodonta, so the two-fingered trunks are still solid evidence.

Such a consistently repeated detail is unlikely to be a mere product of stylization. It is worth saying something about this- ancient people were passionately attentive to the appearance and behavior of animals they coexisted with. Much has been learned about the appearance of extinct animals from ancient art. For example, the Cougnac cave paintings show us the exact coloration of the giant deer Megaloceros; the “lion panel” in Chauvet cave vividly depicts the facial markings of cave lions; and recently discovered petroglyphs in the Amazon have settled the debate over whether or not the bizarre litopternan Macrauchenia possessed a trunk or not. The site Old European Culture extensively covers just how attuned ancient people were to the natural world. They were not ignorant. Their art and mythology were deeply informed by the beautiful mosaic of life in which they were immersed.

Climate

The climatic evidence for late-surviving Palaeoloxodon is likewise strong. The simple fact of the matter is that the regions where the two-fingered bronzes were found are too cold for the Asian elephant to survive, even during the Megathermal Maximum 7,000 years ago. While there were some Asian elephants this far north, they were rare interlopers, with the bulk of the population inhabiting southern China.

Especially relevant given the extinction of its European cousins during the Last Glacial Period, and the final extinction of P. antiquus in Iberia near the beginning of the Last Glacial Maximum, is the geographical difference between Europe and Asia. While Palaeoloxodon bottled up in Iberia would have had nowhere to go as it got colder and colder, the Palaeoloxodon of Eurasia would have been able to move to balmier climates in the south, and then move back north again when the climate warmed. There’s evidence of P. namadicus as far south as Borneo and Java, so they were definitely living in the drowned subcontinent Sundaland for a time.

Fossil Evidence

The fossil evidence is, like all fossils of P. namadicus, fragmentary. Two molars dug out of apparently Holocene strata near a reservoir in Yangyuan. While the authors of the original 1980 paper describing the teeth asserted that they belonged to the Asian elephant, they noted a strong similarity to P. namadicus and P. naumanni. The most telling evidence that the teeth belong to Palaeoloxodon rather than Elephas, and the detail noted by the original authors, is the lozenge-shape of the molar ridges, and the presence of the “loxodont sinus”, which is not present in Elephas. It is only present in Palaeoloxodon and Loxodonta.

Unfortunately, the fossil evidence is by far the weakest line of evidence for the late survival of Palaeoloxodon. Turvey et al (2013) went blow-by-blow over several claims of late-surviving Pleistocene megafauna in China, including P. namadicus. The M3 molar fossil shown by Li et al is presented again in a much clearer photograph, where it resembles a regular Asian elephant molar. The similarities to Palaeoloxodon were just due to the high contrast and blurriness of the photos. The “loxodont sinuses” are attributed to common molar wear. Most damning is that the alleged loxodont sinuses do not appear to be present in the posterior (and thus less-worn) plates of the molar, which they would be if they were true loxodont sinuses. There are multiple other differences listed as well, but I won’t bore you with them because I’m not an elephant dentist and neither are you. Suffice to say, it’s very unlikely that the molar is from Palaeoloxodon.

Finally, and driving the nail in the coffin of this particular fossil, the date was all wrong. While Li et al stated the M3 molar was around 3,700 years old, based on nearby fossil tree trunks, direct carbon dating from the M3 molar itself yields a date of 50,300 years old. So even if it were Palaeoloxodon, it wouldn’t be indicative of late survival.

It’s important to note that despite the presented fossil evidence being thoroughly nixed, this does not mean there is no chance of P. namadicus’s late survival. Lack of fossil evidence does not preclude the presence of a species- there are huge gaps even in the recent Pleistocene fossil record. For example, there are two 6,000 year gaps in the fossil record of Coelodonta antiquitatis- the woolly rhinoceros- from 40-34kya in eastern Europe/southern Siberia, and from 27-21kya in the Urals. It was probably there, we just don’t have fossils of it from those times. Another example is the possibility of late-surviving archaic horses in the Americas, right up to Columbian times- these hypothesized recent wild horses left no fossils, but appear to have left a touch of their ancestry in the genes of modern wild mustangs. And of course, the recently dated human footprints at White Sands, New Mexico are from around 22,000 years ago, thousands of years before the earliest dated human artifacts in North America.

Gaps like this are to be expected. Fossilization is extremely rare, dependent on an animal dying under very specific conditions, like near a river or in a bog, where the body can be quickly buried before scavengers pick it to pieces. The lower the population of a species, the less likely it is that individuals will die under such conditions, so a small relic population just wouldn’t leave many fossils. Most P. namadicus probably died in the middle of the forests they called home, never having a chance to be buried and fossilize.

But they left just enough of their bones in the soil and silt for us to appreciate them today. Whether or not Palaeoloxodon namadicus survived into historic times, or died out at the beginning of the Last Glacial Maximum, it was without a doubt one of the most awe-inspiring creatures to ever live. I believe it did survive into historic times based on the archaeological evidence, but more than that, I hope it survived into historic times. Because it’d be awesome if, not so very long ago, humans had the chance to marvel at these magnificent animals. It’d be awesome if, a mere thousand years before Christ was born, the largest land mammal to ever exist still did.

Sources

First tracks of newborn straight-tusked elephants (Palaeoloxodon antiquus)

Reconstructing the life appearance of a Pleistocene giant: size, shape, sexual dimorphism and ontogeny of Palaeoloxodon antiquus (Proboscidea: Elephantidae) from Neumark-Nord 1 (Germany)

The Pleistocene easternmost distribution in Eurasia of the species associated with the Eemian Palaeoloxodon antiquus assemblage

A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants

Late Middle Pleistocene Elephants from Natodomeri, Kenya and the Disappearance of Elephas (Proboscidea, Mammalia) in Africa

Holocene survival of Late Pleistocene megafauna in China: a critical review of the evidence

Bronze Art Sparks Debate Over the Extinction of the Straight-Tusked Elephant

Palaeogenomes of Eurasian straight-tusked elephants challenge the current view of elephant evolution

Weird skulls of straight-tusked elephants reveal just how many species there were