The Dragonfly of Little Bighorn

Sometime in 1870, a Crow Indian named Goes Ahead traveled to the sacred Wolf Mountains on a vision quest. To demonstrate his total devotion to God, he abstained from food and drink for three days. The pangs of hunger and thirst sharpened his commitment, demonstrating his resolve to give himself up completely to the Creator. He was nineteen.

Called bilisshíissanne in Crow, the purpose of the vision quest was to gain Baaxpée- the sacred power of God Himself. Baaxpée comes in many forms, and different Crows have different reasons for needing it. Whether seeking relief from illness, or desiring to gain strength for battle, the Baaxpée one wishes to attain during his vision quest is unique to that individual.

It is unknown what kind of Baaxpée Goes Ahead was seeking in those lonely mountains, but at some point during his vision quest, something extraordinary happened to him:

After a time, Goes Ahead noticed what he thought was a bird flying very awkwardly, unbalanced, as though the body was too heavy for its wings. It fell twisted at his feet, and he saw that although it had wings, it was not a bird, but more like a serpent— "lizardlike," said Alma. The body was long and heavy, "serpentine," with wings something like a dragonfly's and a tail.

Goes Ahead picked up the body of the strange creature and took it back home with him. His vision quest was complete. He encased the creature in beadwork, and wrapped it in his sacred medicine bundle. Thenceforth, it was his main medicine.

I imagine, perhaps, that upon completing his vision quest, Goes Ahead gathered bearberries from the slopes. What the Indians call kinnikinnick, popular for pipe smoking, he ate simply for their nourishment. Tasteless but filling, their juices slaking a small part of his maddening thirst. If there be springs in those Montana hills, perhaps he laved water from a crisp pool up to his crackled lips. When he was finally satiated, he sat against the ramrod trunk of a ponderosa, and lounged contentedly in the shade of its boughs.

The Wolf Mountains were tranquil, and all was well in the world.

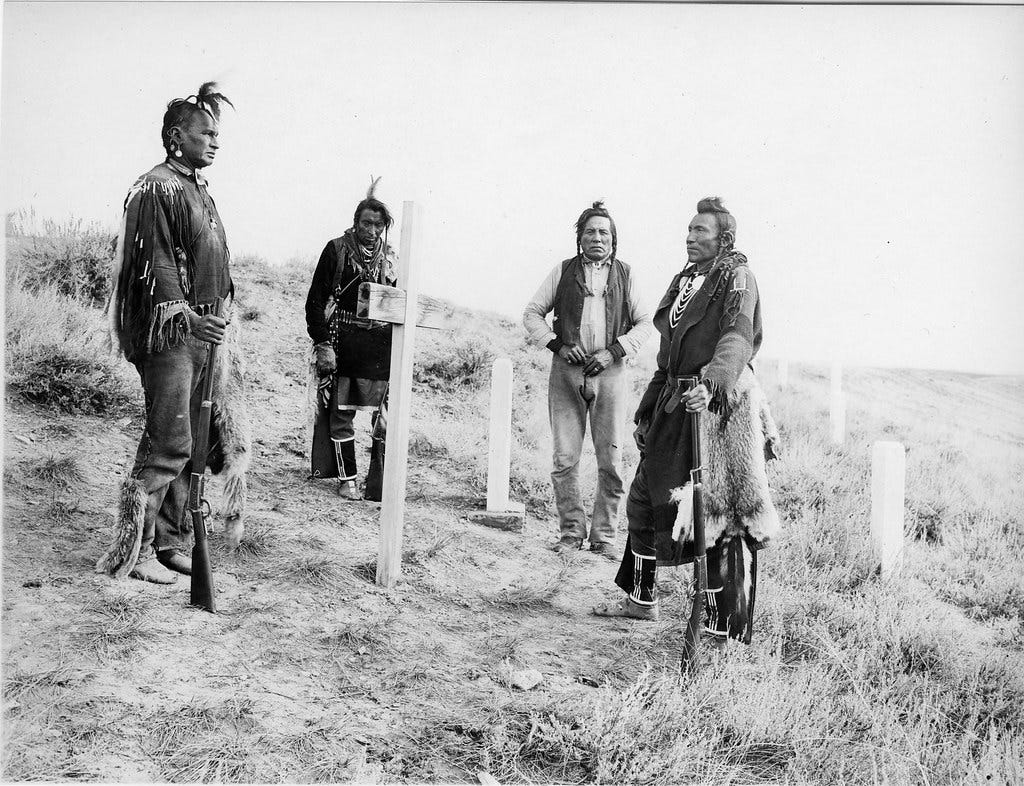

Six years later, in the spring of 1876, a rallying cry went out on the Crow Reservation. Wolves- the Crow term for scouts- were needed. War was in the east. The Lakota Sioux- ancient enemies of the Crow- had invaded the Crow homeland. Together with the Dakotas and the Cheyennes1, the Lakota were running wild throughout southern Montana. Picked men were called out, and Goes Ahead was among the “unlucky braves.” With him were White Swan, Hairy Moccasin, White Man Runs Him, Curley, and their leader Half Yellow Face. Two-Bodies, a half-breed whose “white name” was Mitch Bouyer, was their interpreter.

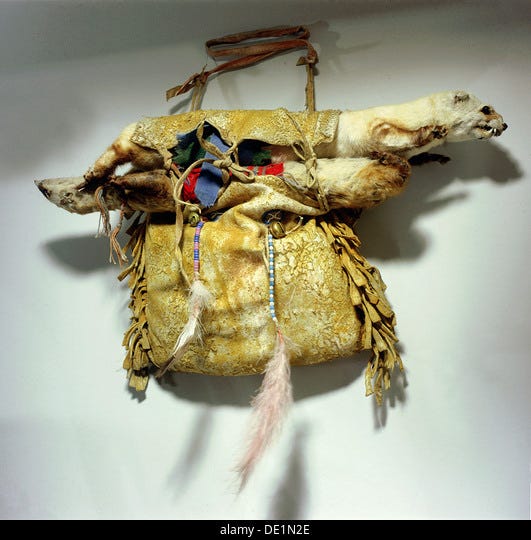

Goes Ahead’s medicine bundle had been his faithful companion since completing his vision quest. The bundle was gorgeous, made of buckskin or trade calico, it would have been ornately beaded and stained with ochre. Always either on his person or hung on a tripod by his teepee, it would be unthinkable for Goes Ahead to leave the bundle behind. It was sacred- the contents equivalent to holy relics. Of course the bundle went with him, down the Yellowstone River to meet a great American chieftain by the name of George Armstrong Custer.

The American camp was near the mouth of the Rosebud Creek. Custer’s tent was the biggest, with a flag flying outside. The general- a hero of the War Between the States, and known to the Crows as Son of the Morning Star- came out and shook hands with each of the Crows. He thanked them for coming immediately, and informed them of the crisis. If the Sioux weren’t stopped, they would overrun the Crow country. “If we win the fight,” Custer said, “everything belonging to the enemy you can take home, for my boys have no use for these things.”

The next morning they broke camp, traveling up the Rosebud Creek until nightfall. Long into the day, the six Crows came upon the first abandoned Sioux encampment. According to Goes Ahead:

We found the first camp of the Cheyenne and Sioux quite a way up the Rosebud. The signs at the deserted village showed that there must be over one hundred buffalo teepees. The trail of the fleeing Indians leading up the Rosebud and to the Little Big Horn country was as clear to us as the roads are today.

The Sioux had had a sun dance here, the frame of the dance lodge still visible in the ground. The next day, they reached a second camp, also abandoned.

At dawn on the fourth day, they reached the Wolf Mountains. The junipers charcoal etchings against a pink matutine canvas. This the day the Crows would prove their worth to Custer. Before they set out into the morning light, Custer warned them to exercise extreme caution- apart from the Sioux, his own men might mistake them for the enemy. To the scouts he bade farewell- “If nothing happens to me, I will look out for you in the future.”

They set out into the hills. Moving without moving. Silent as the fox, limber as otters. Tracking hidden avenues through the bitterbrush, swift and efficient. Carrying their rifles close, careful not to let them snag on errant branches. The slightest sound would betray their presence. Occasionally they stopped, still as stones. Every sense alert. It wasn’t long before they smelled woodsmoke from the Sioux camp, the pined haze tormenting their nostrils as they made their way through the sacred mountains. Perhaps Goes Ahead even passed by the spot where he saw that strange creature, so many years before.

Finally, they made it to the edge of a butte. Cresting the overlook known as the Crow’s nest, they peered down into the biggest Sioux camp they had ever seen. Hundreds of white teepees, shark teeth jutting out of the plains. The woodsmoke from the campfires “seemed like a great mist hanging over the entire Indian camp.” With their Army telescopes, they could see a vast herd of horses grazing where Garryowen is now, 20,000 mustangs on the banks of the Little Bighorn River. The plains of Montana turned that morning into a Serengeti for the Sioux cavalry.

Goes Ahead and the other Crows headed back to Custer to give him the grave news. The Sioux were too many, they said. They warned that there were more Sioux in that village than there were bullets in all his soldiers’ belts.

Custer was arrogant. Custer was brave. Custer thanked the Crows for leading him to the enemy, and released them from his command. His last order to them was to stay out of the fight. Then he attacked.

The Crow scouts stayed. At the most recent of the Sioux camps, a lone teepee had been left standing, to house the body of a slain warrior. Here, at this buffalo hide morgue, the scouts stripped themselves for battle. They stowed their clothes and medicine bundles on the side of the mountain, not expecting to retrieve them. Then they tucked eagle down into their braids, breath feathers, “so they could float onto the other world easier.”

The leader of the Crow scouts, Half Yellow Face, told Custer- “You and I are both going home tonight by a road we do not know.”

As the Crows predicted, there were too many Sioux for Custer to fight. It didn’t help that Custer had split his already thin force into three detachments, none of which were strong enough to stand up to the Sioux by themselves. Custer led one detachment, Major Marcus Reno another, and Captain Frederick Benteen the third. Destruction in detail ensued.

The battle was bloody and desperate. Three of the Crows- Curley, White Swan, and the leader Half Yellow Face- disappeared, and did not participate in the fight. But Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin, and White Man Runs him stayed up on the ridge. There, they watched in horror as the hammer of Reno’s cavalry shattered against the anvil of the Sioux. Chief Gall and Crazy Horse- among many other warriors- led their braves out in a running cavalry battle, scything down Reno’s retreating force as though they were hunting buffalo. Wolves on the fold, baying after the fleeing Americans. Within a few minutes, that part of the battle was over.

Thinking Reno’s men were all dead, the three scouts raced north to rejoin Custer. They kept in defilade, with the ridgeline blocking them from sight of the Sioux, until they came to a gap in the chine where a coulee snakes through, just above the lower fording. Here the three Crows dismounted and fired into the village. Five Lakota horsemen raced through the gulch, decoys sent to lure Custer in. The Crows fired on the horsemen, and took fire in return.

The Crows broke off their engagement and met up with Custer just as he was about to enter the coulee. Custer told the interpreter, Mitch Bouyer, to tell the Crows to head back to the pack mules. “You have done what you agreed to do- brought us to the Sioux camp,” Bouyer said. “Now go back to the pack train and live.”

Then Custer and his men charged down the coulee. Bugles sounded. Hooves pounding against the drum of the earth. A living thunder. The horsemen crashed into the Little Bighorn, attempting to ford. Custer led from the front of the formation, Mitch Bouyer at his side. Both were hit, and both fell into the water. The men fired two volleys, a distress signal that would go unanswered. George Armstrong Custer, Son of the Morning Star, was gone at the battle’s outset2. After that the Crows ran.

They met Benteen’s command back down the ridge and joined him, hastily digging in for the imminent Sioux assault. The ragged remnants of Reno’s command joined them soon after. There was a lot of shooting to the north. Hairy Moccasin said to Benteen- “Do you hear that shooting back where we came from? They're fighting Custer there now.”

Soon, the firing stopped where Custer’s men had been. Then the war cries of the Sioux began moving closer to Benteen, and the might of Gall and Crazy Horse came howling up the hill. Again the battle was bloody and desperate, but the Americans were well dug-in, and they held the enemy at bay.

The fighting ceased at sundown, and the Crows had finally had enough. When asked where they were going, they said they were going to get a drink of water. The scouts rode through the night, retrieving their clothes and precious medicine bundles at some point along the way. They reached the Bighorn by daybreak, where they met General Gibbon and his men. They told him of the disaster, pointing back in the direction of the battle, “where the smoke still hung like a vast cloud.” Gibbon told the Crows they could go home, and then he continued south to relieve Reno and Benteen. Later, they met General Alfred Terry, whose forces were also pouring south. Terry ordered them to come along, but they slipped away once more by claiming they were going to get fresh ponies.

The three scouts made it home, having to fight their own people before successfully convincing each other they were all, in fact, Crows.

Thus ends the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The Blaze

Curiously, the famous battle generated- in a roundabout way- an enduring paleontological mystery. Namely, what was in Goes Ahead’s medicine bundle? What was that strange creature he picked up on his vision quest?

This is important. Nobody would ever have heard this story if Goes Ahead hadn’t participated in the battle. His role as a scout is the only reason we even know his name today. If he hadn’t been there with Custer, he most likely would have simply faded into the obscurity of history, like most people to ever live. Remembered only through a few generations of descendants, the strange details of his vision quest perhaps becoming nothing more than a family legend. But Goes Ahead was a scout for Custer, and so thankfully we do know about his vision quest.

In Fossil Legends of the First Americans, Adrienne Mayor interviewed Goes Ahead’s granddaughter Alma Snell. Alma recounted how, shortly after the battle, Goes Ahead returned to the Wolf Mountains and climbed a tree to carve his blaze- an image of the creature that had come to him during his vision quest. Alma’s father would often point out the ridge to her, but they never searched for the mark themselves. And so the blaze was left in the solitude of the mountains, with only the pines and junipers and chirruping birds for company.

In 1973, Alma Snell happened to meet historian William Boyes at the Custer battlefield. Boyes was particularly interested in Goes Ahead, so Alma told him about the blaze her grandfather had carved. For whatever reason, she did not tell him about Goes Ahead’s vision quest or the fact that the creature was real.

Boyes went up to the ridge and actually found the carving, eight feet up the trunk of a now-withered, methuselaic pine. Here, Boyes did his due diligence as a historian- he took a Polaroid photo of the mark, drew a picture of it, marked it on his map, and sent all of this to Alma. He described the etching as a “winged serpent.”

Regrettably- and perhaps suspiciously, to a skeptic- by the time Mayor conducted her own interview of Alma in 2003, the photograph had gone missing. Mayor managed to get a hold of Boyes, then 75 years old, and he filled in some more details. The image wasn’t the crude trailblaze he had expected, but rather “a careful carving about 15-18 inches long that must have taken hours to make.” I sincerely wish he had taken a second photograph to keep himself, but alas, some secrets wish to remain so.

Since Alma Snell had not told Boyes any details about Goes Ahead’s vision quest or his medicine bundle, Mayor was interested in his description of the mark. He nailed it- “The body was a flying animal, like a lizard with no legs or a thick, blunt snake, but there were 2 wings on each side like what we used to call a Darning Needle [dragonfly].”

Mayor suggests that the “creature” may actually have been a fossil of some kind, and interviewed several paleontologists for their opinions on what it may have been. Their proposals were widely divergent. It might simply have been a fossilized dragonfly. It may have been an unusual bone from a dinosaur or crocodilian, with one paleontologist specifically suggesting it may have been a vertebrae with four ribs splayed out to account for the “wings” of the creature. It may have been a plant fossil whose veins resembled insect wings, or a piece of mummified dinosaur skin. It may even have been a small pterosaur or bat fossil- the oldest known bat fossils are from western Wyoming, not far from the Wolf Mountains. Of course, it may also have just been a modern, naturally mummified bird or animal that Goes Ahead mistook for something else.

Mayor’s own proposal is that, whatever kind of fossil Goes Ahead found, he had a vision of the dying creature falling to earth to explain the finding. He didn’t actually see it fall to the ground- that was a dehydration-induced hallucination. Alma Snell found the fossil explanation possible, saying "It could have been something prehistoric. It was dried out, complete. Over in the Big Horn Mountains, people find other things like that—strange giants with big heads and little bodies petrified, like they were freeze-dried!"

Mayor notes that while the bizarre combination of reptilian and insectoid features may lead one to believe that the creature was entirely imaginary, simply a symptom of hallucinatory dehydration, this certainly wasn’t the case because Goes Ahead picked up its physical body and took it home with him. He found something.

Bacoritse

We’ll return to potential explanations for the creature in a moment, but right now I want to discuss the fossil traditions of the Crow, because some context will help the reader better understand why Mayor suggested Goes Ahead found a fossil in the first place. You see, the Crow were very well aware that fossils are special.

This was not a modern scientific understanding, of course. The Crow had no knowledge of evolutionary theory or geologic time, but they understood plainly that fossils, called bacoritse, were the remains of creatures that are no more.

A brief overview of Crow religious beliefs is in order. This is a little complicated, so bear with me. The Crow are a monotheistic people, believing in one omnipotent Creator, often affably referred to as Old Man Coyote. Yet they also believe the world is full of spirits. Spirits can take many forms- the stars are held in high regard, and bones are respected and feared. Animal spirits are the most potent, and usually Crows seek the manifestation of an animal spirit on their vision quests.

Recall, the vision quest is about seeking Baaxpée, the sacred power of God. To receive Baaxpée, a Crow needs a spiritual intercessor to bestow it. The spirits are not deities- they fulfill a similar role to what angels and saints do in Christianity, acting as intermediaries between God and man.3 The fasting of the vision quest is to demonstrate total commitment to God, so that a passing spirit may take pity and lend- not give, but lend- the Crow some of their Baaxpée. It’s important to note that the spirits don’t possess Baaxpée in their own right. It all comes from God, His breath passing through all things through all of time.

Now, the contents of the medicine bundle- that is, the medicine- are considered physical manifestations of Baaxpée, formally known as Xapáaliia. This is why Goes Ahead took the body of that strange winged animal with him- that was his medicine, his Baaxpée. This is also where Mayor got the idea that the creature he found was a fossil, because fossils are also infused with Baaxpée.

Being infused with such sacred power, fossils were considered powerful talismans- many Crows claimed their bacoritse could summon the bison, a tradition that carries across multiple Plains peoples. Marine fossils are especially revered, with ammonites, baculites, and dentalia “tusk shells” being fairly common components in medicine bundles. Other fossils could be carried as well- it’s likely that some bundles incorporated bones from dinosaurs like Tenontosaurus, Sauropelta, and sickle-clawed Deinonychus. Recognized as fragile, usually the fossil medicine would be carefully encased in beads and calfskin hide. They would be brought out when the user had need of their power, and many of the bacoritse ammonites have been rubbed glossy from decades of use.

Ammonites were also favored for use as necklace amulets. When used in this manner, they would often be covered in red ochre paint, the bloodrose pigment bringing out the fibonacci spiral of the shell. Certainly, exquisitely rare ammonites that had been opalised or pyritized would be even more valued as medicines.

Goes Ahead wasn’t even the only man at the Battle of the Little Bighorn who may have had a fossil with him. White Man Runs Him, the Crow scout who fought alongside Goes Ahead, had a painted ammonite in his own medicine bundle, adorned with red and white wool fringe and a constellation of beads. The Lakota chief Gall, who largely carried the day for the Sioux, likewise had a large ammonite pendant on his necklace, draped in beads and tusk shells, attesting to the amulet’s power.

Completing our discussion of Crow fossil traditions4, we can move on to the final explanation for what Goes Ahead saw on his vision quest…

Meganeura?

There’s one more explanation for what Goes Ahead saw that I neglected to mention earlier. In the book Dragons or Dinosaurs? author Darek Isaacs asserts- I’m not making this up- that the creature Goes Ahead saw on his vision quest wasn’t a fossil or a hallucinatory experience, but rather a real live Meganeura moyni. Formerly alive, rather, as the creature fell dead at Goes Ahead’s feet.

At a glance, the description seems to fit fairly well. Meganeura was a griffinfly, related to dragonflies but much, much larger. With a wingspan of 25-28 inches, it’s the largest known flying insect- about the same size a merlin and three times bigger than the biggest modern dragonfly. Goes Ahead’s carving was somewhere between 15-18 inches- smaller than Meganeura, but we could postulate that the size of the drawing was constrained by the tree. Nevertheless, if not exactly the scale of Meganeura, there were other meganeurids closer to this size.

There are a few significant differences between Meganeura and Goes Ahead’s carving, however. The eyes of the carving are much too small. Instead of being two dots at the front of the head, Meganeura’s eyes were great, green globes encompassing the entirety of either side of the head, similar to modern dragonflies.

The serpentine features of Goes Ahead’s carving are also harder to account for. Dragonfly abdomens can bend somewhat- they need to in order to mate and lay their eggs- but in normal flight they don’t bend in the undulating, wave-like pattern Goes Ahead carved into the tree. I suppose when Goes Ahead picked up the body, he may have noticed the abdomen bend and incorporated this into his drawing, but this is speculation on my part.

Alma Snell described the creature’s body as “lizardlike”, which I’m assuming is referring to the texture of the skin. But dragonflies aren’t scaly. Their exoskeletons are shiny, and in this regard can appear similar to some lizards or snakes, but the differences are still immediately clear. Meganeura and meganeurids in general did not resemble lizards; they were essentially just upscaled dragonflies. Still, one could speculate that the texture of Meganeura’s exoskeleton may have been different and perhaps more “serpentine” than a normal dragonfly.

So, it seems pretty cut and dry, right? Goes Ahead saw a Meganeura, picked it up, and took it home.

There’s one major problem with this theory- Meganeura is extinct. It’s been extinct since the end of the Carboniferous, 300 million years ago. This was long, long before the first dinosaurs appeared. There were five major extinction events between Meganeura and the first dinosaurs. A greater chasm of time separated Meganeura from the first dinosaurs- 67 million years- than separates us from the last dinosaurs.

The world of the Carboniferous was very different than the one we live in today. Atmospheric oxygen levels were much higher, 35% versus 21% today, largely due to the unprecedented spread of trees. Enormous forests covered virtually the entire world, but when the trees died, they just sat there. The microbes and fungi required to process cellulose and lignin hadn’t evolved yet, so the trees couldn’t decompose. Trees sucked in CO2 and released tons of O2, but the CO2 stored in dead trees wasn’t being released back into the atmosphere.

All of this extra oxygen enabled insects- including Meganeura- to reach much larger sizes than those attainable by living insects, because arthropod respiration limits their size. With more oxygen, they were able to respirate more efficiently and could grow larger. Insects simply cannot reach such large sizes today, because the atmosphere puts a hard cap on how big they can get.

Major scientific difficulties notwithstanding, Isaacs draws the comparison. I should say right now, Isaacs is a Young Earth Creationist, and the aim of his book is to discredit evolutionary theory by describing anomalies such as this, where a case could be made for extinct creatures persisting long after the date of their generally accepted extinctions, to be observed by humans in historic times. I do not believe he succeeds in this task, but he does make many interesting points. I certainly wouldn’t ever have had the creativity to think that Goes Ahead might’ve picked up a specimen from a relic population of Meganeura.

Despite the goofiness of suggesting Meganeura survived in Montana in the 1870s, Isaacs actually makes some very good arguments about the flaws of the idea that Goes Ahead found a fossil, rather than a living creature. Specifically, he takes issue with the assumption that Goes Ahead simply misinterpreted what he was seeing, and on this I concur completely. Goes Ahead wasn’t an idiot. It’s insulting to the man’s intelligence to suggest he made such an obvious error, mistaking a crocodile vertebrae for some sort of dragonfly.

And mere condescension is the best case scenario- at worst, they’re calling him a liar, saying he saw one thing when he actually saw something completely different. Regardless of whatever he did see, his blaze does not evoke the image of a fossil vertebrae or a mummied sparrow.

Another issue with the fossil explanation is that Goes Ahead saw the creature alive. Remember, it came flying into view- shakily, like it couldn’t quite handle itself in our atmosphere- and dropped to the ground dead. Goes Ahead specifically did not describe it as a bacoritse. It wasn’t a fossil- it was a living creature that died before him.

While we may- if we wish- still dismiss the whole incident as a dehydrated hallucination, there’s simply no good reason to believe that it was a fossil. This is another issue Isaacs has with the paleontological explanations- they go into it assuming it was a fossil, when in reality we don’t know what it was, because we don’t have the medicine bundle to examine.

Personally, I don’t believe it was a fossil, and I also don’t believe Goes Ahead was, in Isaac’s words “so mentally compromised that he could not even decipher between a giant dragonfly that fell at his feet and a plant fossil that he might have tripped over.”

So what was it?

I think we can safely discard the idea that it was a fossil, unless we are to presume Goes Ahead was a moron, which I don’t believe he was. And we can also discard the idea that it was a late-surviving Meganeura, for… a multitude of reasons. One could bring out a litany of evidences showing that the Earth is older than 6,000 years, but for now all we need is the fact that Meganeura couldn’t survive today due to the differences in oxygen content between the Carboniferous and now.

This brings me to my own theory. You can laugh at it if you wish, and it may be just as silly as suggesting a population of Meganeuras was still alive in the 1870s, but I propose it nonetheless. Hear me out-

Time portal.

Think about it for a second. If we assume some sort of temporal anomaly, it rescues Isaacs’ Meganeura theory from the perils of robust geologic evidence, and also explains why the creature died immediately upon entering our era. It was a Meganeura, and it couldn’t breathe in our comparatively deoxygenated atmosphere. The reason it was “flying very awkwardly” and “unbalanced” is because it was suffocating.

Obviously this requires more theoretical framework than Mayor’s neat fossil explanation- namely, a belief in things like portals and time travel. But I think it’s at least possible. Maybe not likely, but possible.

It also wouldn’t be the only incident of bizarre, otherworldy insects appearing inexplicably. In 1827, a horde of black, one-inch insects appeared in Pokroff, Russia after a snowstorm. They seemed to be perfectly adapted to the snow in a way unlike any other insect, even burrowing directly into ice. The bugs handled temperatures up to eight degrees below zero perfectly well, but died within minutes when exposed to indoor warmth. This was a well-documented event, recorded in the Edinburgh Journal of Science.

The wonderful paranormal podcast Dead Rabbit Radio5 posited that the Pokroff insects may have come from a different timeline, or dimension- someplace else- and showed up on Earth at precisely the proper latitude and in the proper season where they could survive for awhile. Not permanently, because they all died eventually and have never been seen again. But it would parallel inversely to the appearance of Goes Ahead’s Meganeura- unfortunately for that bug, it couldn’t survive for any length of time in our world. Wherever it came from- be it some alien planet or the Earth’s own past- the conditions here, today, were inhospitable, so it died.

This would be the expected outcome of random temporal anomalies. If you were teleported back in time, to any random time in Earth’s history, most likely you’d be immediately pulped by the immense water pressure, because more often than not you’d be teleported miles underwater. For more than half of Earth’s history you would have immediately been poisoned and suffocated by the atmosphere, or melted in the protoplanetary magma. This applies to all creatures.

What happened to Goes Ahead’s Meganeura might be startlingly common, if we assume temporal anomalies are real- they just go unobserved more often than not, and Goes Ahead was lucky enough to witness such an event. A creature appearing at this point in our history and being able to thrive would be the exception, not the rule.

So, the mystery ends more or less where it began. We are no closer to figuring out the identity of the creature Goes Ahead found on his vision quest, without evoking unsatisfactory or wildly improbable explanations. Whatever it was, though, it was important to him, and the Baaxpée it provided may have even saved his life in the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Sadly, we will never know what was really contained within Goes Ahead’s medicine bundle- whether it was a fossil or the body of a more recently deceased creature. The blaze is likely long gone- Alma Snell and others have tried to find it using William Boyes’s map, but many forest fires have ravaged the mountains since 1973. And the bundle likewise is no more. Goes Ahead threw it into the Little Bighorn River on the day he was baptized.

Adrienne Mayor recounts that day:

[I]n about 1900 he tossed his medicine bundle into the Little Bighorn River, swollen with the March thaw. As the women in the tribe wailed, he threw it away, along with all his other sacred possessions of bygone days, when he was baptized as a Christian.

Sources

Fossil Legends of the First Americans by Adrienne Mayor

Dragons or Dinosaurs? Creation or Evolution? by Darek Isaacs

Son of the Morning Star: Custer and the Little Bighorn by Evan S. Connell

Goes Ahead's Story of the Battle, #1

Goes Ahead's Story of the Battle, #2

From ‘100 Voices’ – Pretty Shield’s Story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn

C-SPAN Cities Tour - Billings: Battle of the Little Bighorn

Cool video on Meganeura and the Carboniferous in general

The Insects Will Devour Us All (Dead Rabbit Radio episode on the Pokroff insects)

The Cheyenne are not a Sioux people, but for the sake of brevity throughout the rest of the essay I refer to the Indian forces collectively as “the Sioux”

This account is not the mainstream narrative of the battle, in which Custer died on Custer Hill. However, it is actually robustly supported by many eyewitnesses- Americans, Lakotas, and the Crow scouts. I’ve included links in the sources for anyone interested in reading further just about the battle.

It’s not a 1-1 comparison- there is more control involved in the Crow belief. So, if you gained Baaxpée from a bison spirit, you can actively use the power of the bison to perform certain tasks- anything from gaining strength to granting wishes. In Christianity, the intercession of saints and angels is entirely passive- they pray on your behalf, but cannot help you directly. Overall, however, the similarities between the two are striking.

As they relate to medicine bundles, at least. The Crow have a rich fossil legendarium, which I may return to in a later essay.

If you’re interested in the paranormal, you’re doing yourself a disservice if you don’t listen to this podcast.