In the previous essay, we talked about Leaellynasaura, possibly the cutest dinosaur to ever live. Here, we will be discussing the south polar world she lived in, and some of the various species she coexisted with.

The Polar World

As stated previously, during the early Cretaceous the supercontinent Gondwana was coming apart at the seams. Western Gondwana- consisting of South America, Africa, and Arabia- had already largely split apart by the Albian epoch, 113 million years ago, with only a narrow thread holding Africa and South America together. On the other hand, eastern Gondwana- comprising Antarctica, Australia, India, Madagascar, and the failed continents Zealandia and Kerguelen- remained largely intact. India and Madagascar had just cleaved off, and Zealandia was beginning to calve, but Australia and Antarctica remained joined together, isolated from the rest of the world by the south pole. Despite remaining geographically contiguous, however, the ultimate separation of Antarctica and Australia was well underway- an enormous rift valley existed between the two continents.

This rift valley was not a barren wasteland, like Antarctica today, despite the fact that it lay deep within the Antarctic Circle. This was a younger, warmer world. Dense subpolar forests covered the landscape, the copses separated by the labyrinthine channels of a swift river that dashed through the region. The delta was vast, plaited, speckled with sandbars, thicketed islands, and oxbow lakes left over from when the brooding river had changed her mind about which way to flow. Overall, the valley’s environment probably wasn’t too dissimilar to the temperate Valdivian and Magellanic rainforests that still exist in southern Chile.

Here, in the wood at the bottom of the world, much of the flora would be unrecognizable to us, present in our time only as attenuated groves in relic ranges. Araucarias, gingkoes, Wollemi pines, tree ferns, southern beeches, and evergreen podocarps dominated the canopy. Most of these trees have very scattered ranges today, like the flat-topped araucarias which have been reduced to fragmented pockets in far-flung lands like Argentina and New Caledonia. Some are even Lazarus taxa- the Wollemi Pine was thought to have been long extinct until a single copse of them was found alive and well in 1994, growing in a ravine north of Sydney.

In the understory, ferns, horsetails, clubmosses, liverworts, and cycads quilted the valley floor in variegated hues of green. Instead of grasses, which did not exist in the early Cretaceous, the ancestors of the bizarre megaherbs that still grow on New Zealand and her subantarctic islands may have blanketed the meadows and moors of the region. Finally, some of the earliest angiosperms evolved in Gondwana around this time, punctuating the lush garden with white flowers eerily similar to modern magnolias and buttercups. All of these strange plants would have made up the bulk of the diets for the herbivorous dinosaurs living in the polar realm.

Small-bodied Ornithopods

In the previous essay, I mentioned how Leaellynasaura lived alongside several other small, elasmarian ornithopods. Small-bodied ornithopods were by far the most numerous animals in the south polar region, with fully half of the dinosaur taxa from southeastern Australia being elasmarians. Leaellynasaura coexisted with three other species- Atlascopcosaurus, Diluvicursor, and Qantassaurus- and there are five other elasmarians known to have lived before or after the Albian epoch. We won’t go into exhaustive detail on them here, because frankly there just isn’t that much information about the others that we didn’t already cover in the Leaellynasaura piece.

All of these animals lived in the same braided river valley as Leaellynasaura, which their ancestors had entered sometime in the early Jurassic. Some of them may have had feathers, for the same heat-retention reasons as Leaellynasaura. Some of them probably burrowed as well- you may recall that the fossil burrows found on the Otway Coast didn’t have any dinosaur remains in them, so really they could have belonged to any of these little elasmarians. If burrowing was a basal trait to ornithopods, it’s possible they all did, since none of them were large enough to migrate. The abundance of these small ornithopods suggests that they were thick on the ground and likely the dominant herbivores, as opposed to other regions in the Cretaceous, where hadrosaurs and ceratopsians dominated.

They also must have all had similar diets, though likely with some niche specialization to maintain ecological harmony. Similar to how in the modern Serengeti, wildebeest and zebras are able to coexist perfectly well, migrating together in massive herds with no competition. The reason is simple: zebras prefer longer grasses than wildebeest. Maybe Diluvicursor and Leaellynasaura preferred to dine on different types of ferns or megaherbs.

Muttaburrasaurus

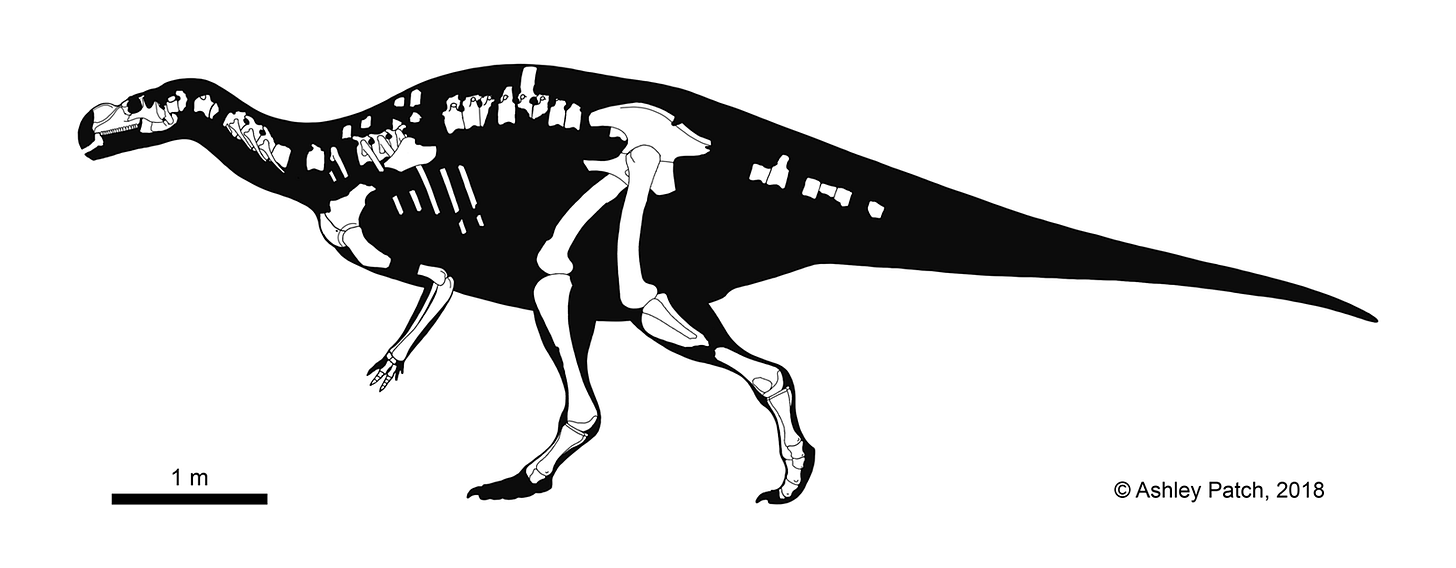

While the menagerie of elasmarians scampered through the magellanic undergrowth, a much larger herbivore was browsing the canopy. Muttaburrasaurus langdoni was a 3 ton, 8 meter giant, capable of browsing trees up to 3 meters off the ground when rearing up. Discovered in Queensland, it’s known from fairly complete remains- in fact, it’s one of Australia’s most completely preserved dinosaurs- but its phylogenetic position is a little uncertain. It may have been an exceptionally large elasmarian, growing to fill the vacant “hadrosaur” niche in east Gondwana. But most paleontologists believe it was basal to the rhabdodont family. Rhabdodonts were the next rung up the ornithopod family tree after elasmarians; they were cousins and progenitors to the more advanced iguanodonts and (later) hadrosaurs of the northern hemisphere. Primarily they lived in western Gondwana and what would become Europe, but the branch that led to Muttaburrasaurus had arrived in Australia back in the Jurassic, a ghost lineage on account of the continent’s poor Jurassic fossil record.

Interestingly, much later in the Cretaceous, hadrosaurs managed to migrate southward into the shattered remnants of Gondwana, penetrating first into South America and then Antarctica. The Americas were briefly connected in the late Cretaceous, allowing a biotic interchange to take place. It ended when Central America broke apart again, rendering South America an island continent until the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, 61 million years later. It’s unknown whether or not the invading hadrosaurs ever made it to Australia, but given how primitive the rhabdodonts were, Muttaburrasaurus’s descendants probably wouldn’t have fared too well in direct competition with them. Any contest probably wouldn’t have lasted too long regardless- hadrosaurs first appear in the Antarctic fossil record during the Maastrichtian, the very last epoch of the Cretaceous, right before Earth had a fateful encounter with an asteroid at Chicxulub.

Muttaburrasaurus was so primitive it wasn’t even capable of quadrupedal motion, with reduced forelimbs more akin to those of the elasmarians than the hadrosauriforms in its own weight class- hadrosaur hands were essentially hooves, allowing for a very efficient quadrupedal gait. Ecologically, however, it was more similar to the hadrosaurs, and unlike its elasmarian cousins, Muttaburrasaurus was definitely large enough to migrate north for the winter. And it probably did, just like how its Arctic hadrosaur counterpart Edmontosaurus is known to have migrated south from Alaska.

The dentition of Muttaburrasaurus was likewise primitive, lacking the extremely efficient “dental battery” used by hadrosaurs to quickly replace worn teeth. While the dental battery reabsorbed old teeth into the replacement teeth for maximum usage, in Muttaburrasaurus new teeth grew directly under the old ones, one generation at a time. It couldn’t chew its food, only shear and slice, which would have helped it to process tougher vegetation like cycads. Back in the 1980s, paleontologist Ralph Molnar suggested that it may have even eaten carrion from time to time, shearing chunks of meat from carcasses, but he later discarded this theory.

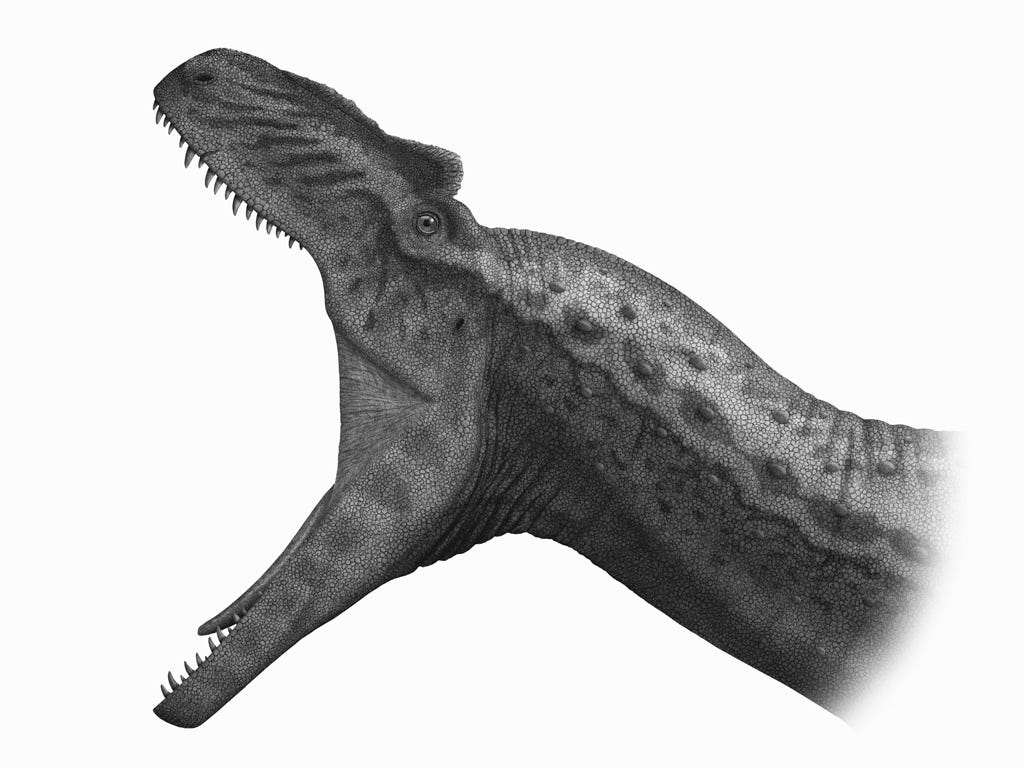

Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of Muttaburrasaurus is its very pronounced nasal bulge. This enlarged nasal cavity is theorized to have been used for communication, acting as a resonating chamber which would allow the animal to honk or bellow to other Muttaburrasaurus across long distances. It may also have been sexually dimorphic; a stouter, possibly more functional analog to the elaborate head crests of hadrosaurs. This has implications for the animal’s behavior- if the nasal bulge was sexually dimorphic, it may have been used in courtship rituals, similar to the gular pouches of frigatebirds and the greater sage grouse.

It’s unclear if Muttaburrasaurus was a herd animal or not. They’ve never been found together, but this doesn’t necessarily mean they didn’t congregate in herds. Many fossils of more recently extinct species, like mammoths and archaic horses, are found alone, but we know these to have been herd animals. The solo specimens we find are simply individuals who were left behind by their herds after they passed away. Other large ornithopods, like Iguanodon and Edmontosaurus, are known to have lived in herds, so it’s likely Muttaburrasaurus did as well. Relating to the animal’s polar environment, large Arctic herbivores in our time like reindeer and muskox are herd animals, and emperor penguins congregate in huge colonies to help conserve warmth.

Cheetah of the Cretaceous

Due to the fragmentary nature of Australian and Antarctic fossil beds, we don’t know very much about the predatory theropods that lived there. Cryolophosaurus was an Antarctic dilophosaur with a bizarre, pompadour head-crest. But it lived during the early Jurassic, long before the early/mid-Cretaceous timeframe we are examining here. We have the tibia of a theropod called Kakuru and the femur of Timimus, both of which are of unclear affinities. There are fragmentary remains of an elaphrosaur, a bizarre group of theropods with toothless mouths and long, flamingo-like necks, and we also have the footprints of a very tiny genus called Skartopus, which stood a mere 8 inches at the hip. And that’s about it. We’re at a loss for most of the theropod genera that lived in the south polar region during the early Cretaceous. There certainly were many theropods there, we just don’t have good fossils from most of them.

But we know about the megaraptors.

By Australian standards, Australovenator wintonensis is known from fairly complete remains. The holotype specimen, named Banjo, is the most complete carnivorous dinosaur known from the continent. Australovenator lived in Queensland during the Cenomanian epoch of the late Cretaceous, just a few million years past the Aptian-Albian epochs we’ve been examining thus far. However, the megaraptoran Rapator, known from a single left hand bone, lived during the Albian and may be synonymous with Australovenator. Additionally, a wickedly sharp megaraptoran claw has been found in Albian sediments along the Otway Coast in southern Victoria. So megaraptorans were definitely around in the Albian; even if they weren’t Australovenator itself, they were certainly ancestral to it.

Australovenator was a formidable predator. It was 20 feet long, standing 6’6” at the hip. Weighing between 1,100 and 2,200lbs, it was a lightweight among theropod hunters, and its long, powerful legs would have rapidly propelled it across the valleys in pursuit of prey. Scott Hocknell, who described the genus in 2009, dubbed Australovenator “the cheetah of its time.”

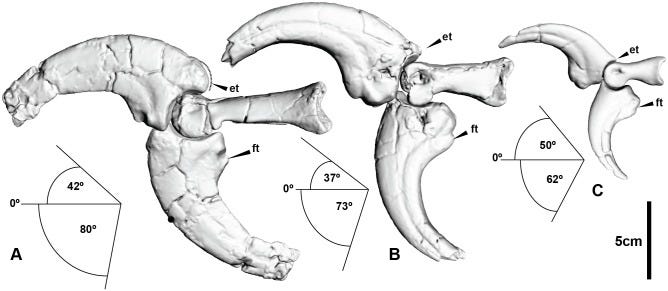

The arms of Australovenator are the most completely known remains, and have been studied extensively. While the animal’s jaw was very gracile, with small teeth unsuited for biting or slicing into large prey, the forearms were robust and surprisingly flexible. The arms were capable of a greater range of motion than most theropods, able to flex in a 78° arc at the elbow, more similar to dromaeosaurs like Bambiraptor (68°) and Deinonychus (99°) than any of the other megaraptorans or carcharodontosaurs to which Australovenator was most closely related.

Australovenator’s fingers were naturally hyperextended, with the karambit-like claws exhibiting a very wide arc of motion unlike any other theropod. The only one that even comes close is the early Jurassic Dilophosaurus, and Australovenator’s degree of extension (42° hyperextension, 80° flexion) is much greater, although soft tissue probably limited it somewhat. It should be noted here that, despite their impressive range of motion, Australovenator’s hands were actually quite primitive compared to other Cretaceous theropods, and the hyperextension specifically is almost totally absent from coelurosaurs (the group including tyrannosaurs and maniraptorans). The articulation of the fingers is more similar to the Jurassic allosaurs than it is to any later coelurosaur.

The wrists were also remarkably flexible, able to flex further inward than just about any other theropod. All of this points to the arms of Australovenator being its main weapons. It seems to have killed not by biting, but by grabbing prey with its powerful arms and slashing or stabbing it to death with its claws. Once the prey was dispatched, the arms and hyperextended claws were used to grip the prey and bring it up to the animal’s mouth.

Australovenator’s legs were likewise strong and robust. As stated, it was probably a swift runner more than capable of chasing down prey, but it may have also used its legs for combat. In the holotype specimen, one of the bones in the second toe has a pathology where it is splayed outward just a little bit. White et al (2016) speculated that the injury may have been due to repeated kicking. Many large birds, such as herons, cassowaries, and emus, use their legs as weapons during intraspecific combat or when they feel threatened, jump-kicking their opponents until they back off. People have been killed by cassowaries, and zookeepers have been mauled by them. It would make sense for Australovenator to engage in similar behavior.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the second toe of Australovenator is the one with the pathology, and in extant ratites, the second toe is the most flexible and the one primarily used for combat. This is speculative of course- the pathology could have been from a nasty trip, or stubbing it in a crevice- but it being caused by Australovenator viciously kicking rivals in intraspecific combat is just as likely.

The phylogenetic position of Australovenator is, like just about every dinosaur in Australia, a bit of a mystery. It was initially classified as a basal allosauroid, in light of its primitive traits, but was later reclassified as a megaraptoran. The megaraptorans were still allosauroids, just further up the tree. Interestingly, the early Cretaceous age of Rapator suggests that megaraptorans may have originated in Australia or Antarctica, radiating out from there into South America later in the Cretaceous when temperatures warmed enough for them to cross the pole. It’s important to remember this- despite the temperature being warmer in the Cretaceous than today, the Antarctic Circle was still a formidable biogeographic barrier that had kept Australia isolated from the rest of Gondwana since the early Jurassic, so the megaraptorans were penned up for awhile.

More recently, Australovenator and all other megaraptorans have been reclassified as tyrannosauroids. Personally, I disagree with this assignment and I don’t believe it will hold up. Australovenator has so many primitive characteristics- specifically in the non-coelurosaurian hands- that the previous allosauroid assignment is more plausible. Tyrannosauroids are only known from fragmentary, highly contentious material in Gondwana. They were Laurasian creatures, dominating the northern hemisphere, and no other Laurasian taxa are known from Australia in the early Cretaceous.

Regardless of its classification, Australovenator was almost certainly the apex predator of its environment. And, assuming the megaraptorans did evolve in eastern Gondwana, they did quite well once the climate warmed enough for them to cross the pole in the mid-Cretaceous, populating South America even against stiff competition from abelisaurs and the much larger carcharodontosaurs.

One could even cautiously suggest that the megaraptorans outcompeted the carcharodontosaurs, directly causing their extinction. The first megaraptorans appear in South America right on the heels of the carcharodontosaur extinction. This is highly speculative on my part. Carcharodontosaurs were much larger than megaraptorans and specialized in hunting giant titanosaur sauropods, whereas Australovenator and the megaraptorans were likely more generalist hunters. However, Australovenator is associated with sauropod remains in Australia, so they may well have been hunting similar prey. It’s also possible the carcharodontosaurs went extinct due to the climate changes of the Bonarelli Event (discussed below), and the megaraptorans simply swooped in to fill the vacant niche.

Relic Allosaurus

In addition to Australovenator, there is some evidence suggesting that Allosaurus, the famous predator that went extinct at the end of the Jurassic, may have survived into the early Cretaceous in Australia. Allosaurus, most famously known from western North America, was present across much of the world, ranging from Montana to France. It was one of the apex predators of the Late Jurassic, a very tough animal that is known to have persisted under extreme climatic conditions. At one site in Utah, there’s evidence of a cataclysmic drought, and the upper layers of the formation are almost entirely Allosaurus, suggesting that it was the last species present in the final stage of dying. If any dinosaur was going to refuse to die when the reaper came knocking, it would have been Allosaurus.

A single anklebone found in Victoria has been considered representative of a relic species of Allosaurus. Don’t laugh- paleontologists can tell a lot from even a single bone. When Ralph Molnar first posited back in 1981 that the bone belonged to Allosaurus, S.P. Welles wrote a rebuttal listing nineteen features of just this single ankle bone that he believed precluded it from being an allosaur. Molnar then wrote a rebuttal, addressing each of these nineteen points. More recently the specimen has also been assigned as an abelisaur, but it’s still hotly debated.

What’s relevant to us is this- despite being similar to an allosaur ankle, the bone is much smaller than the ankles of typical allosaurs, suggesting that it may have belonged to a pygmy species, probably an insular dwarf that had been isolated from the rest of the world since the late Jurassic. This is quite possible- there were allosaurids living in southern Gondwana during the Jurassic, because they later diversified into the megaraptorans and the carcharodontosaurs. It wouldn’t be much of a stretch for one such allosaurid to have been stranded on an island, and to have survived when others in its family either went extinct or diversified into new, unfamiliar forms.

If it was indeed a pygmy Allosaurus, it would have been the last of its kind, living over twenty million years after the genera disappeared elsewhere in the world. Biogeographically isolated from the rest of the supercontinent since the early Jurassic, eastern Gondwana would have been a perfect place for this relic species to cling on, long outstaying its time on the globe in forlorn refugium.

The Sauropod Assemblage

Besides small-bodied ornithopods, the long-necked sauropods are the most numerous dinosaurs known from Australia. They were also the largest by far, thunderously treading the lush forests and river valleys that would someday become bone-dry outback. In the mid-Cretaceous, Australia was home to a diverse array of titanosaurs, which included some of the largest land animals to ever live. It’s debated where exactly in the titanosaur family tree the Australian ones were nested, but we know they were in there somewhere.

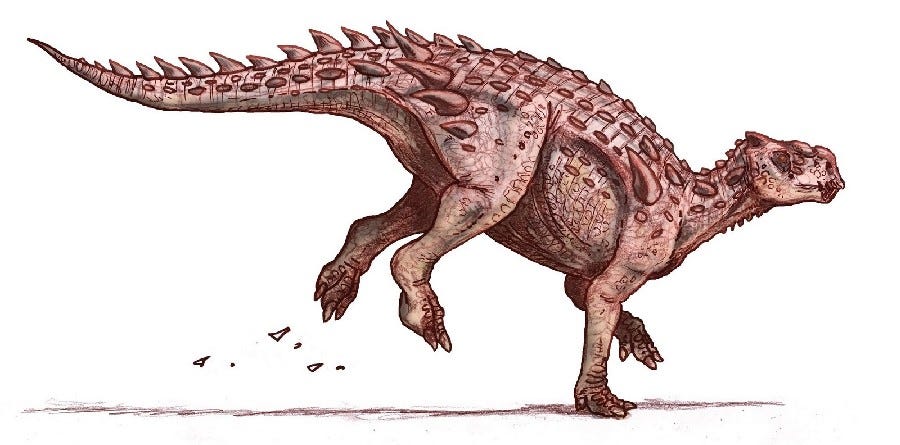

One of the Australian titanosaurs was Diamantinsaurus, which would have been around 2.5-3 meters tall at the shoulder, and 15-16 meters long. Given the robustness of its known skeletal remains, it’s likely this was a bulky animal, but it was actually on the smaller side as far as titanosaurs go- Argentinosaurus was well over double its length and height. It may or may not have had the osteoderms depicted in the artwork above- some titanosaurs had them, but no osteoderms have been found with the few Diamantinasaurus fossils discovered thus far.

Interestingly, a second specimen of Diamantinasaurus included a nearly-complete endocast. Like most sauropods, Diamantinasaurus had a tiny brain, just 4.6 inches long. Sauropods in general were likely very unintelligent, with extremely low brain-to-body ratios. Big brains just weren’t necessary to their lifestyle, which was simply shoveling plant matter into their mouths as efficiently as possible.

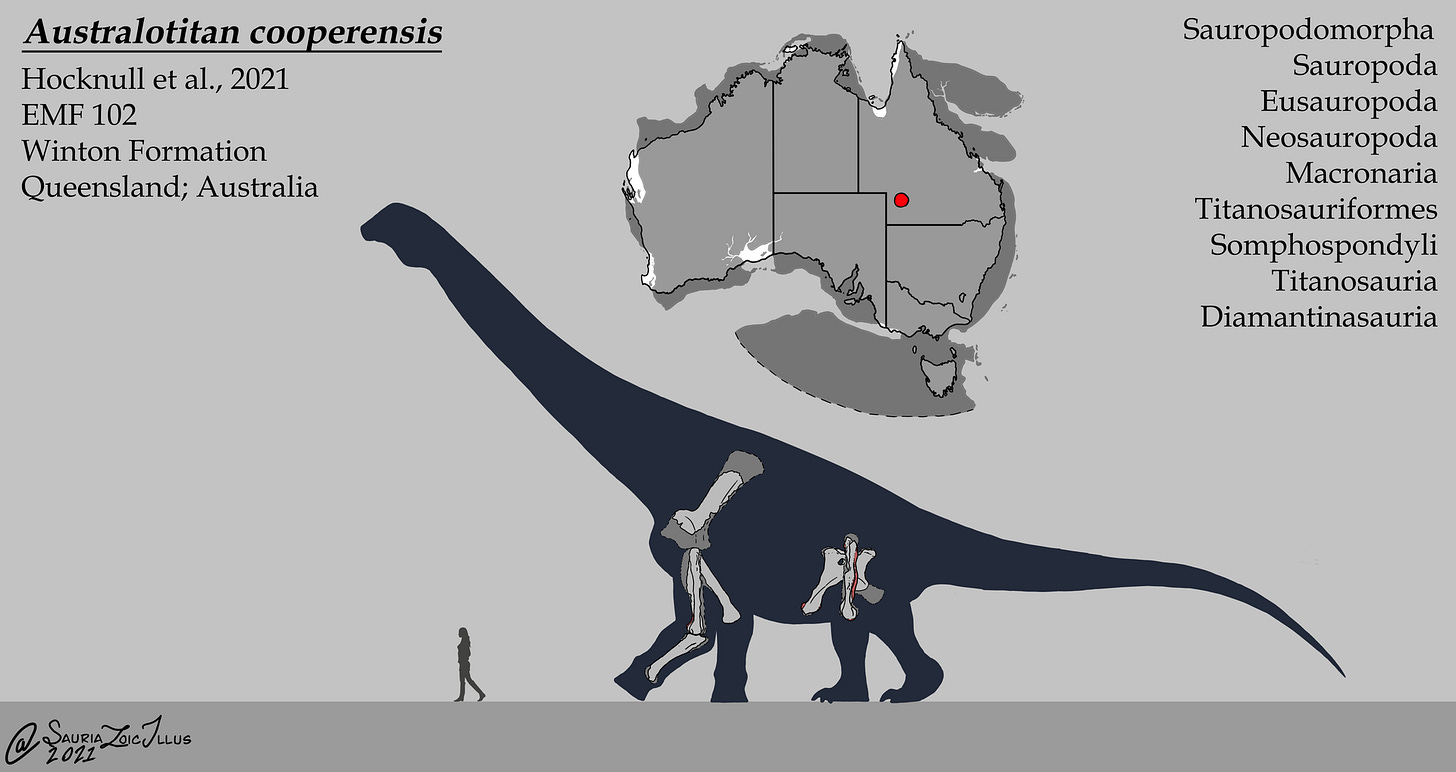

Diamantinasaurus coexisted with several other large titanosaurs- Savannasaurus, Wintonotitan- but the largest was Australotitan. Probably measuring 30 meters long and 6.5 meters at the hip, Australotitan was described in 2021 and confirmed the presence of giant titanosaurs in eastern Gondwana, where they had previously been unknown.

None of these sauropods appear to have lived in the polar region, however. They were all discovered in Queensland, which was outside the Antarctic Circle during the Cretaceous. Not one is known from Victoria. And all of the sauropods except Austrosaurus, which we’ll discuss in a moment, are known from later-Cretaceous sediments, dating to the Cenomanian and Turonian epochs, right after the Aptian and Albian.

Titanosaurs seem to have crossed over the pole from South America during the Bonarelli Event, around 91 million years ago. Undersea volcanoes unleashed an enormous amount of carbon dioxide, causing global temperatures to rise enough for the frigid biogeographic barrier of the Antarctic Circle to melt away, reuniting the biotas of eastern and western Gondwana for the first time since the early Jurassic. The Bonarelli Event caused a whole biotic interchange. Some species that crossed into new lands did quite well, like the titanosaurs and the megaraptorans, while many native species suffered in the face of new competition.

Another weird relic animal living in Australia at this time was Austrosaurus. It’s unusual for being a large sauropod from the early Cretaceous, the late Albian, just before the Bonarelli Event is believed to have occurred. Most paleontologists today consider it to be just another titanosaur, and it may well have been one given its proximity to the Bonarelli Event. But initially it was classified as a cetiosaur, a primitive group that had a wide range during the early and middle Jurassic, but went extinct in all other locations at the end of the middle Jurassic. If it was a primitive cetiosaur, it may not have fared well against the derived titanosaurs when they arrived after the Bonarelli Event.

Minmi & Kunbarrasaurus

Minmi has always been one of my favorite dinosaurs. The name is just wonderful- Minmi. Rolls right off the tongue. A bit of trivia- for a long time, Minmi was the shortest dinosaur name. It was a small ankylosaur, and the most basal ankylosaur known as yet. Measuring around 3 meters long, a scant 1 meter tall, and probably weighing about 660lbs, it was a midget compared to later forms like Ankylosaurus, an 8 meter, 8 ton giant from Late Cretaceous North America.

Minmi lived in Queensland during the very early Cretaceous, 133-120mya, pretty much at the end of the earth. As previously stated, Queensland wasn’t in the Antarctic Circle during the Cretaceous- it was an archipelago just above it, and isolated from the rest of the world by it. Only a narrow peninsula connected it to the rest of Australia, making it the perfect location for unusual, primitive genera such as Minmi to persist when they would have been outcompeted or evolved into more competitive forms elsewhere.

Minmi was a very basal ankylosaur, comparatively lacking in armor compared to the Laurasian ankylosaurs- the ankylosaurids and the nodosaurids. It still possessed armor, but it wasn’t well developed. The neat rows of bony ossicles and osteoderms peppering the animal’s back and upper legs hardly encased it, unlike the protective carapaces of more derived ankylosaurs.

The reason for this lighter coat of armor appears to be due to the fact that Minmi wasn’t relying on it for defense against predators. Ankylosaurids and nodosaurids were the Cretaceous equivalent of tanks, heavily armored and armed thanks to their flexible tails that, in ankylosaurids, had heavy clubs of bone at the end. If approached by a predator, they could stand their ground and fight. Minmi, on the other hand, bolted when under threat. Its legs were much longer than in other ankylosaurs, suggesting that it ran or galloped away from predators.

The species name, Minmi paravertebra, is in reference to an odd feature of the animal’s skeleton. Along the dorsal vertebrae, there were elongated rods of bone positioned horizontally to the vertebrae. They aren’t part of the vertebrae, but rather were positioned on top of and nearly parallel to them. Each rod attached to a transverse process and faces toward the tail. Three of these paravertebra were found in the holotype specimen- there was certainly a fourth that wasn’t preserved, and there may well have been others further down the back. They appear to have been attachment points for muscles, but their function is unknown.

Molnar (1980) suggested that the paravertebra may have been used to support the dorsal armor- that is, the large armor osteoderms along Minmi’s back, as opposed to the smaller, circular ossicles of ventral armor on the animal’s flanks- but they were unable to confirm if this was actually the case. Interestingly, Molnar posited that if the paravertebra were supporting the dorsal armor, then the armor was probably mobile to some degree, able to be raised and lowered.

This is a very unique feature, unknown in any other dinosaur, and the possible functions of raising the dorsal armor are tantalizing. It may have been used as a threat display, similar to the modern porcupine raising its normally flattened quills to make itself look larger and spikier to predators, or a dog raising its hackles in aggression. It may also have been a sexual display feature. Devastatingly for this essay, I was unable to find any illustrations of Minmi showing the armor raised up.

The second Australian ankylosaur was actually considered a species of Minmi for a long time, before being reassigned to its own genus. Kunbarrasaurus is the most completely known Australian dinosaur, with most of its body preserved in articulation- that is, in the position the animal died in, instead of it being a discombobulated jumble of bones.

Kunbarrasaurus was much like Minmi in most respects- indeed, being more completely known, most reconstructions of Minmi have actually been based on Kunbarrasaurus. Both were primitive ankylosaurs with thin coats of armor. Kunbarrasaurus lived later than Minmi, solidly in the Albian epoch from 105-99mya, and is known to have possessed small scutes even on the underside of its belly, an unusual trait that appears to have been lost in later ankylosaurs.

The stomach contents of the Kunbarrasaurus holotype were preserved, so we know its last meal consisted of ferns, leaves, seeds, and fruit. That last one is important. The very first flowering- that is, fruiting- plants appeared during the Early Cretaceous, so dinosaurs were able to digest them right from the get-go. For a long time, there was a theory that the spread of flowering plants contributed to the extinction of the dinosaurs, with the herbivorous ones only being able to eat conifers and cycads, staring in bewilderment at the new, indigestible fruits and flowers. Kunbarrasaurus handily disproves this notion.

The full tails of Minmi and Kunbarrasaurus aren’t known, so it’s unclear whether or not they had tail clubs, like later ankylosaurids. The recently discovered Chilean ankylosaur Stegouros didn’t have a traditional tail club, but rather possessed a very distinctive empennage resembling an Aztec war club, the macuahuitl. The Antarctic ankylosaur Antarctopelta, while known from fragmentary remains, appears to have possessed a similar weapon. These two were closely related to Minmi and Kunbarrasaurus, together forming the clade parankylosauria, a very basal group originating in the Jurassic that nevertheless persisted right up until the end of the Cretaceous in the polar regions of Gondwana. So it’s entirely possible that the Australian ankylosaurs had these macuahuitl tail weapons as well. It’s also possible they didn’t have any tail weaponry at all, and simply ran away from their predators. Until we find more fossils, we won’t know.

Due to the length of this post going far beyond what I originally intended, there will be a third and final part to this series posted later in the week, before Christmas. We will leave behind the dinosaurs and explore some of the other bizarre Cretaceous creatures that once called the Australo-Antarctic rift valley home…

Sources

South Polar region of the Cretaceous- Wikipedia

Global Biogeography, by J.C. Briggs (1995)

Biogeographical network analysis of Cretaceous Australian dinosaurs, Kubo (2020)

The Lost Valley Between Australia and Antarctica

Australian Museum page on Muttaburrasaurus

Observations on the Australian ornithopod dinosaur, Muttaburrasaurus

Wikipedia page on Muttaburrasaurus

Museum fossil leads to discovery of new 110 million year old dinosaur: Australia’s first elaphrosaur

Forearm Range of Motion in Australovenator wintonensis (Theropoda, Megaraptoridae)

Wikipedia page on Australovenator

Second specimen of the Late Cretaceous Australian sauropod dinosaur Diamantinasaurus matildae provides new anatomical information on the skull and neck of early titanosaurs, Poropat et al (2020)

Minmi page on Australian Museum

Dan’s Dinosaur Info- Minmi paravertebra

This bizarre armored dinosaur had a uniquely bladed tail weapon