Previously, we’ve discussed the dinosaurian fauna of east Gondwana, specifically looking at Australia. At this point, however, we are leaving behind the dinosaurs. Now, in the final part of this series, we are going to discuss some of the extremely bizarre, non-dinosaurian animals that lived at the south pole during the early Cretaceous. Welcome to wonderland.

The Last Temnospondyl

As previously stated, there was once a high-energy braided river flowing through the Antarcto-Australian rift valley. It was fed by springs and, periodically, glacial meltwater from Tasmania, which anchored the southeastern end of the valley. Tasmania was actually in the middle of this rifting event; Antarctica tried to take the island with it. But the rift failed, leaving the shallow Bass Strait separating it from mainland Australia. From the valley floor, it must have appeared as a great plutonic mass jutting up from the ground, a stone monarch forever feeding its river daughter. Frigid brooks gushing forth from perched aquifers, bounding down the mossy. boulder-strewn hillsides to swell the mighty river’s myriad tributaries. The water was cold, here at the bottom of the world, and giant amphibians prowled the black streams.

Koolasuchus cleelandi superficially resembled a giant salamander, but wasn’t closely related to them. Hellbenders eat crayfish. Koolasuchus ate dinosaurs.

Koolasuchus was a temnospondyl, a group of amphibians that originated in the early Carboniferous, 330 million years ago, and became incredibly widespread during the Permian. Most “temnos” went extinct in the Permian-Triassic extinction, the cataclysmic Great Dying in which 70% of land vertebrates went extinct. But a few temnos survived, prospering in the Triassic. Then they were walloped again, harder this time, in the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, wherein the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province erupted, deluging 11 million square kilometers of central Pangaea in lava. This time, only one group of temnos scraped through the cataclysm- the brachyopoids. There weren’t very many of them, hanging on in out of the way locations, like Australia and far eastern Laurasia during the Jurassic. The brachyopoids were further subdivided into the brachyopids and the chigutisaurs. Koolasuchus belonged to the second group, and was the very last one, persisting into the early Cretaceous.

Koolasuchus really did look like a giant salamander. Based on its large jaws- the most completely known skeletal elements- it’s estimated to have been around 3-4 meters long and probably weighed half a ton when mature. Being an amphibian, it may have had a larval form we don’t yet know about. It had a broad, flat, shovel-shaped head which was significantly wider than the body, such that its head was vaguely reminiscent of a hammerhead shark. The beady eyes were situated atop a menacingly wide mouth, its gaping maw filled with rows of needlelike teeth. These teeth were perfect for dispatching Koolasuchus’s preferred prey- the plethora of little elasmarian dinosaurs living in southern Australia at the time.

Given its large size and aquatic lifestyle, Koolasuchus is thought to have convergently evolved with crocodiles to fill in the “underwater ambush predator” niche. It wouldn’t have been a one-to-one convergence- as a giant amphibian, Koolasuchus probably lived almost its entire life in the water, like modern giant salamanders. Indeed, its lifestyle may have been more of a mixture of a crocodile and a Wels catfish, being an apex predator of fish while occasionally snapping up dinosaurs coming to drink at the river.

And it certainly didn’t haul itself onto the wet gravel banks to bask like a crocodile, as this would dry out its thin, respirating skin. It could probably come onto land for short stretches, however- there is a fossil trackway in Lesotho preserving the path of a large temnospondyl moving on land. The temno that left these tracks was about the size of Koolasuchus, and appears to have had a sprawled posture, dragging its body along the ground using only its fingertips. It was a very primitive, inefficient means of locomotion, hindered by the animal’s giant skull and heavy shoulders. Thus, terrestrial locomotion was probably only useful for moving Koolasuchus between streams and ponds, or back into the water after lunging at a hapless dinosaur.

Generally though, it was similar to a crocodilian. The reason Koolasuchus was able to fill in the crocodile niche in the first place is simple- there were no crocodiles in Australia yet. The water was too cold. Crocodilians cannot survive in temperatures below 45° Fahrenheit- they actually lose their balance in the water and drown- and the waters of south polar Australia were certainly this cold during the long winter night, if not year round.

Amphibians, on the other hand, are capable of handling extraordinarily cold weather. Southern leopard frogs are dormant in winter, but they don’t hibernate- they shelter at the bottoms of unfrozen lakes and ponds, lazily swimming in circles throughout the cold season. Wood frogs can survive being near-literally frozen solid. When they hibernate, up to 2/3 of their body’s water content freezes. The remaining third is kept liquid by a natural antifreeze in the frog’s bloodstream, consisting of glucose and urea, which prevents the individual cells in the vital organs from freezing. They do this for up to seven months in Alaska, and when the summer morning finally dawns they awaken from their frozen slumbers just fine.

It’s likely Koolasuchus had similar adaptations to help it survive the long months of darkness at the south pole. It may have remained awake at the bottom of rivers, lazily brooding in the frigid currents while it waited for spring. Or it may have hibernated in the mud, its blood turned to a coagulate slurry, dreaming about the terror-stricken eyes of a doomed Leaellynasaura struggling in its mouth.

Alas, Koolasuchus’s time ran out near the end of the Aptian epoch, when the global climate warmed dramatically in the Bonarelli Event. We discussed this briefly last time- undersea volcanism dramatically increased the global temperature enough to allow many animals which had previously been rebuffed by cold temperatures to traverse the Antarctic Circle for the first time. Some dinosaurs, like the titanosaurs and megaraptorans, were winners in the Bonarelli Event, dramatically expanding their ranges. Koolasuchus was one of the losers. It lost out to new competition, competition from “a whole warmer aquatic fauna” according to Warren et al (1997).

Most directly, crocodilians were finally able to cross over the pole. This alone would have doomed Koolasuchus. Crocodilians were just better at being underwater ambush predators, and swiftly outcompeted the last temno for prey. Crocodilians do not coexist with Koolasuchus in the fossil record- they first appear on the very heels of its extinction. And while adult temnos were being outcompeted for prey, their young also suffered. Suction-feeding fish first appeared in Australia around this time, and were likely efficient predators of Koolasuchus eggs and larvae. New diseases may also have been introduced by warmer-climate amphibians crossing the pole into Australia, to which Koolasuchus would have had no immunity.

Finally, to really kick Koolasuchus while it’s down, the changing climate itself may have negatively affected the giant temno. Modern giant salamanders in China and Japan are very temperature-sensitive, ceasing to feed at temperatures above 68° F, so Koolasuchus may have suffered from the heat. Speculatively, if they were anything like modern giant salamanders, they may have even starved themselves, mistakenly thinking winter was coming, when in reality it wouldn’t come again for 86 million years.

The Iron Dragon

While Koolasuchus plied the waterways of the south polar realm, pterosaurs ruled the air. In the early Cretaceous, the dominant group in east Gondwana remained the anhanguerids, which were in sharp decline elsewhere in the world. Formerly ranging across the globe, they were among the last pterosaurs to possess teeth, with the rest of the various pterosaur families losing theirs in favor of sharp bills.

The largest known Australian pterosaur was the Albian-aged Thapunngaka shawi. Discovered in northwest Queensland, it’s estimated- based on extrapolation from related pterosaurs- to have had a wingspan of up to 23 feet. The species’ name derives from the aboriginal Wanamara language, translating to “spear mouth.” Paleontologist Tim Richards, who described the species in 2019, stated:

“The new pterosaur, which we named Thapunngaka shawi, would have been a fearsome beast, with a spear-like mouth and a wingspan around seven metres. It was essentially just a skull with a long neck, bolted on a pair of long wings. This thing would have been quite savage. It would have cast a great shadow over some quivering little dinosaurs who wouldn’t have heard them coming until it was too late.”

This aside, anhanguerids are generally believed to have been aerial fishers, skimming back and forth across the water surface and dipping their beaks in to catch fish, turtles, squid, and baby marine reptiles. Central Queensland at this time was not a desolate outback, but rather the coastline of the shallow Eromanga Sea, which reached far inland and nearly split Australia in two.

However, the anhanguerids may also have dined on baby dinosaurs as well, given their abundance on the ground. Living in a mammal-dominated world, where even the most r-selected species tend to have a small number of offspring, it can be difficult for us to imagine how abundant dinosaurs were. Every year there were potentially billions of newly hatched baby dinosaurs scampering around. This annual hatching would have been a feeding bonanza for pterosaurs, mammals, and other dinosaurs, and only a very tiny number of dinosaurs survived to adulthood because of it.

The very last anhanguerid in the world was Ferrodraco. The name translates to “iron dragon” and was chosen because the skeleton was found in ironstone sediments. Living in the Cenomanian epoch, 96 million years ago, Ferrodraco was a relic. By this point, the toothless pteranodonts had taken over everywhere else, and Australia once again found itself the last refuge of an ancient bloodline.

Ferrodraco was smaller than Thapunngaka, but still boasted an impressive 13ft wingspan. Like Thapunngaka, it’s only known from incomplete remains, and size estimates are extrapolated based on other anhanguerids. The Australian fossil record for pterosaurs is pitifully incomplete- paleontologist Dave Unwin said “You could put all the fossil material [of Australian pterosaurs] in a handbag.”

The extinction of the anhanguerids coincided with the Bonarelli Event. In addition to raising global temperatures, undersea volcanism also caused an ocean anoxic event, warming the seas and starving them of oxygen. This caused a decline in fish populations, and the anhanguerids couldn’t survive the loss of their food supply. Ferrodraco itself, despite dating to after the Bonarelli Event, may not have actually survived the marine collapse- if the surviving population was too small, it may have undergone a genetic meltdown, fading out a short while later.

Both Thapunngaka and Ferrodraco- and anhanguerids in general- sported thin crests on the keels of their snouts. The function of these crests isn’t known, but most likely they were used for display purposes. They may have been sexually dimorphic as well- one sex possibly possessing larger and/or more colorful crests to attract mates.

Steropodon and other mammals

Steropodon is one of the most interesting mammals of the Mesozoic. It’s known only from a single lower jaw fragment with three molars, but the dentition is enough to tell us that Steropodon was a monotreme, the group of egg-laying mammals to which modern platypuses and echidnas belong. It’s also the oldest known monotreme, dating back 110 million years to the mid-Albian. It probably would have been about the same size as a modern platypus- around a foot and a half long- and thus quite large for a Mesozoic mammal.

The presence of a mandibular canal, present in the platypus and its extinct relatives, suggests that Steropodon may have had a bill as well. Its relationship to the living platypus is unclear; we don’t know if Steropodon was ancestral to the platypus, or if it was in its own family and simply acquired a bill via convergent evolution. We do know that Steropodon’s molars were more robust and deeply rooted than those of living platypuses, so it seems that despite their identical size, Steropodon could take down larger prey than its modern relative. Fish, as opposed to insects and crayfish.

Bizarrely, Australia seems to have been home exclusively to monotremes during the Cretaceous. Think about this for a moment. Placental mammals- that’s you, me, your dog, the rabbit your dog is chasing, the horses in the Derby, the monkeys at the zoo- didn’t even exist in the early Cretaceous. The entire mammalian world consisted of marsupials and monotremes, and a few other families that have long since gone extinct, such as the allotheres. Just like how marsupials today are largely relegated to Australia, in the early Cretaceous the continent was a weird backwater where the egg-laying mammals dominated. Marsupials don’t appear to have penetrated Australia until much, much later, crossing over from South America during the Paleocene Thermal Maximum, when the planet was hot enough for there to be rainforests at the south pole.

It’s difficult to convey how isolated Australia was from the rest of the Mesozoic world. During the early Cretaceous, 33% of vertebrate taxa in Australia were endemic- they lived in Australia, and nowhere else. Monotremes dominated the mammalian landscape, and there were all kinds of relic dinosaurs running around, but we haven’t even gotten to the real relics yet.

Besides Steropodon, most of the other Cretaceous mammals in Australia were very, very small, easily fitting in the palm of your hand, and were likely insectivores. They may have been preyed upon by small pterosaurs, or the tiny theropod Skartopus, which seems to have ranged in size between a parrot and a hawk, perfectly sized for snacking on monotremes.

The Cynodonts

There were even stranger mammaliaforms in Gondwana. I say “mammaliaforms” instead of mammals, because we are no longer discussing true mammals. The creatures we will be discussing in the next two sections were stem-mammals, the group of “mammal-like reptiles” that immediately preceded true mammals.

The first stem-mammals we’ll look at are the cynodonts. Cynodonts were tough- they made it through the Permian-Triassic apocalypse, like the temnospondyls, and they diversified in the Triassic, like the temnospondyls. Unlike the temnospondyls, they’re still around today, sort of. You are a cynodont, technically, along with all other living mammals, because we descended from them and so are nested within the cynodont clade. Similar to how birds are dinosaurs due to common descent, but not all dinosaurs are birds. Likewise, cynodonts themselves were not mammals, instead standing just outside the mammalian umbrella. And not all cynodonts became mammals either. Some were perfectly content to remain as cynodonts, long after true mammals were on the scene.

It is worth saying something about this- evolution is not a video game. There is no such thing as “leveling up” in evolutionary terms. There is no “goal” beyond reproduction, and there is no such thing as an “ultimate lifeform” or any other pop culture nonsense. Evolution is a game of whatever works- if an adaptation helps an organism to reproduce, that adaptation will likely carry on into the next generation. If the adaptation is detrimental, that organism will most likely die without offspring. It’s that simple. Some of the cynodonts eventually became you and me, but some remained in what we call a “transitional” state, because for them, in the environment they inhabited, those “transitional” adaptations between reptile and mammal were good enough.

With that said, for the most part cynodonts died out during the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event. A few tiny ones, the globe-spanning tritylodonts, held on into the early Cretaceous. Some Gondwanan cynodonts appear to have held on much longer. Southeastern Gondwana- South America, South Africa, and Antarctica- had always been the global core of cynodont diversification, and so it’s only fitting that the last members of this ancient lineage made their final stand here. The very last non-mammalian cynodonts, the gondwanatherians, persisted well into the Miocene, a mere 17 million years ago, in South America. The little meerket-like gondwanathere Patagonia peregrina is the last known survivor.

Gondwanatheres aren’t specifically known from Australia, but it can be reasonably inferred that they lived there too, due to their presence on every other Gondwanan landmass. However, despite the lack of gondwanatherians specifically, cynodonts are known from Australia. Fragmentary cynodont fossils- maybe gondwanatheres, maybe tritylodonts- dating to the Albian-early Cenomanian epochs, around 100mya, have been found in the Winton Formation of central Queensland. These Australian cynodonts would have been the relics of an earlier radiation of cynodonts across all of Gondwana. They seem to have lived in New Zealand as well, though their range across Zealandia and whether or not these kiwi cynodonts persisted into the Cenozoic is presently unknown.

One of the Australian cynodonts, Kollikodon ritchiei, is known only from an opalised lower jaw and a fragment of the upper jaw. Nevertheless, the jaw has much to say. The molars of Kollikodon were large, and clearly specialized for crushing its food, perhaps shellfish. The molars were also huge, suggesting the total size of the animal could have been up to a meter, making Kollikodon one of the largest mammaliaforms of the Mesozoic.

I should say right now that the assignment of Kollikodon as a cynodont- along with the gondwanatherians- is highly contentious. They’re all known from very fragmentary remains, and some researchers believe them to have actually been proper mammals more closely related to monotremes, or, in the case of the gondwanatheres, closer to allotheres. Nevertheless, recent analyses have nested Kollikodon and the gondwanatheres both within the cynodont clade haramiyida, and that’s the assignment we are favoring here. And this possibility of late-surviving cynodonts in Australia leads us directly into our next potential late-survivor…

The Dicynodont

Probably the most unusual find out of early Cretaceous sediments in Australia is a series of skull fragments from a possible dicynodont. Dicynodonts, as their name suggests, were related to cynodonts, though only distantly. They were both non-mammalian therapsids, and they both survived the P-T apocalypse. This is about where their similarities end. Cynodonts and dicynodonts looked nothing alike. While cynodonts often superficially resembled rodents- or, earlier in their evolutionary history, canines and felines- the dicynodonts looked downright alien. Reflecting their transitional status between reptiles and mammals, their hind legs were held upright like a mammal, while their forelimbs bent outward at the elbow like a lizard. Their bodies would have appeared vaguely familiar, with the larger forms resembling rhinos or hippos, and the smallest ones looking similar to mole rats. But their heads would be more at home on Barsoom than Earth. They had horny, toothless beaks like turtles or finches, and only retained two canine teeth as a large set of tusks, probably used for rooting around in the dirt for tubers.

Unlike the cynodonts, no living animals are descended from dicynodonts. They went extinct hard and final at the end of the Triassic, with the niches they occupied soon being filled by dinosaurs like stegosaurs and, later on, the ceratopsians.

However, in east Gondwana, the dicynodonts may have survived much longer. Much, much longer. A hundred million years longer, into the early Cretaceous.

Six skull fragments, discovered in June 1915 near Alderley Station in north-central Queensland, which sat forgotten in a museum drawer for the better part of a century, were analyzed by Tony Thulborn and Susan Turner in 2003. The pair found the skull fragments, dug out of early Cretaceous sediments, to be the unmistakable remains of a dicynodont. The most telling fragment was a left maxilla (upper jawbone) with a large tusk-stump still attached.

There are many other diagnostic traits that support the bones belonging to a dicynodont, and not a dinosaur or a mammal. The tusk displayed wear and tear typical of dicynodonts; the root is covered in a film of cement-like tissue similar to other dicynodonts; enamel coverage is reduced like in a tusk; the tusk’s internal structure matches the very unique pattern present only in dicynodonts; and finally abrasion marks match what dicynodonts were using their tusks for, rooting around in the dirt for food. One particularly noteworthy trait is the presence of a tusk itself- dicynodonts are the only animals, besides true mammals, to possess tusks at all. There are no tusked dinosaurs that the maxilla could possibly belong to.

The authors state unequivocally:

“In summary, all available evidence supports identification of the Alderley material as a late-surviving dicynodont, and we are unable to find even a single feature that would weaken or contradict that identification. If the Alderley material had originated from Permian or Triassic rocks it would probably be accepted without hesitation as a perfectly ordinary dicynodont. That response greeted the first dicynodont specimens from Antarctica, isolated maxillae which, in nearly every respect, are anatomically equivalent to the example we describe here.”

This is a shocking revelation. A Cretaceous dicynodont- living over 100 million years past the date we believe they went extinct- would be a more impressive example of a Lazarus taxa than if someone found a living sauropod dinosaur in the African jungle, with only 65 million years having passed since their extinction.

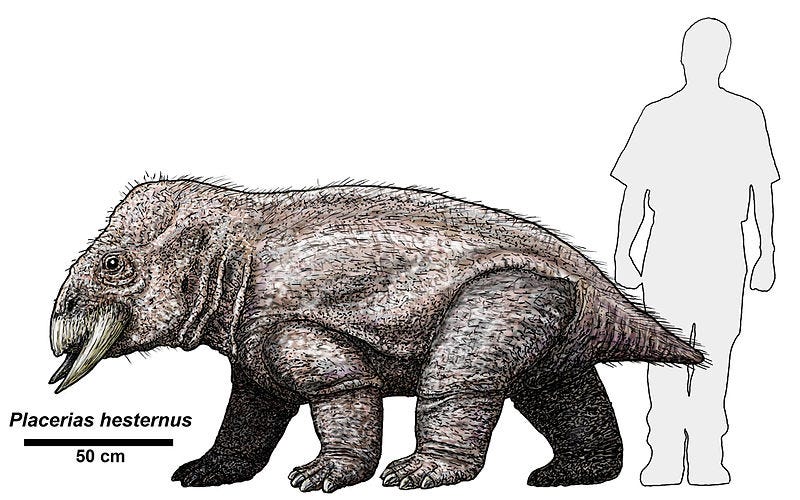

The animal these bones belonged to was not particularly small- the complete skull would have measured sixteen inches long. Smaller than cow-like Placerias, but longer than pig-sized Ufudocyclops. If Old MacDonald had a dicynodont, this one would be the alien sheep-stand in, in terms of general length and height at least. In reality, it would have been much stockier and heavier than a sheep. The skull fragment may also have belonged to a juvenile, however, in which case it remains unclear how big it might have gotten.

The dicynodonts, as stated in Thulborn & Turner, don’t have an exact analogue among modern animals, but they do show a convergence with ceratopsian dinosaurs. There is a superficial resemblance- one had twin tusks protruding from the mouth, the other horns from the skull- but the similarities are deeper than this. They were both robust quadrupeds with horny beaks, they both had very large skulls and powerful jaws, and they even both shared an expanded ilium correlating with a shorter tail. In light of these similarities, Thulborn & Turner suggested that the relic population of dicynodonts in east Gondwana fulfilled the same niche that ceratopsians did in Laurasia.

The assignment of these remains to a dicynodont has been contentious, and with good reason, given what an extraordinary claim it is. A 2019 study, Knutsen & Oerlmans, reassessed the skull fragments and found that they actually belonged to the diprotodont Nototherium. Diprotodonts were megafaunal marsupials that lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the late Pleistocene. What? How can that be, with so many obvious dicynodont traits in the skull? And how could the timeframe have been so laughably wrong, off by 105 million years?

The researchers thoroughly reexamined each of the claims for the dicynodont identity of the fossils, and found them all to be either not as diagnostic as Thulborn & Turner believed, or to be uncertain. They X-rayed the bones, attempted to date the remains using zircon and trace element levels, and used synchrotron microtomography (a menacingly big word) to obtain very detailed cross-sections of the tusk and maxilla.

Out of the battery of tests they ran, the trace element analysis was the most useful, and the point on which the study hangs its hat. The beryllium 9 content of the alleged dicynodont bone clustered more closely to a diprotodont maxilla found in the same area by the same guy a few months earlier, than it did to a Cretaceous-aged ichthyosaur, also from the same area. The ichthyosaur sample had double the beryllium content, while the “dicynodont” and the diprotodont clustered very closely together. As for the sediments it was dug out of being Cretaceous-aged? There appears to be a Pliocene-Pleistocene fossil bed in the area that went unnoticed previously, because a kangaroo fossil was found in the same area at the same time, as well as the aforementioned diprotodont maxilla.

So, mystery solved right? Dicynodonts died at the end of the Triassic, just as previously believed. Well, probably. I will say this- if dicynodonts did survive anywhere past the T-J boundary, it would have been this exact location. Two recurring themes throughout this essay have been the isolation of Australia, and the presence of relic organisms. There were relic temnospondyls, relic cynodonts, relic mammals, and many relic dinosaurs. A relic dicynodont would fit right in with this weird, out-of-time faunal assemblage. But, more than that, the location where the alleged dicynodont was discovered- north central Queensland- was itself isolated from east Gondwana during the early Cretaceous, as we’ve mentioned repeatedly. I remind the reader one last time, this was the remotest sticks of the planet, separated from literally everywhere else by newborn seaways and by the pole. Sometimes it wasn’t even connected to the rest of Australia, instead being separated by a shallow sea.

The tale of the dicynodont is also noteworthy because it’s a wonderful example of what can happen when researchers look into museum archives. These “dicynodont” bones were just sitting in a drawer for nearly a century. They were discovered in 1915 and it took until 2003 for someone to take another look at them, and it sparked this mystery. Every museum in the world is like this. There are Indiana Jones warehouses of fossils that have never been examined, collecting dust in the basements of all the museums and institutions on the planet. There could very well be real Cretaceous-aged dicynodont remains, broken into fragments by the eons but still identifiable as dicynodonts, sitting in a museum drawer somewhere. But they’ve never examined because they were filed away and nobody ever bothered with them again. That’s something that could happen.

Coda

Thus we come to the end of our overview of the Australo-Antarctic yesterworld. We see a bizarre faunal assemblage, sharing affinities with other Gondwanan fauna, yet made unique by its epoch-spanning isolation due to the impassable barrier of the Antarctic Circle. And while sharing kinship with other Gondwanan fauna, the Australian biota was totally isolated from Laurasia, as though the northern and southern hemispheres were different planets. We see the biogeographic barrier of the pole break down due to undersea volcanism in the middle Cretaceous, which resulted in the destruction of the isolated Australian biota and its replacement by a new, more generalized Gondwanan ecology. Some of the Australian taxa did rather well, and others suffered extinction.

This is only a brief overview of the weirdest parts of the Australian ecology- we neglected to examine any of the bizarre marine life, including freshwater plesiosaurs and the bony palaeoniscid fishes that were holdovers from the Silurian. And we certainly don’t have any space here to examine the possibility of polar dinosaurs having survived the infamous KT extinction event that wiped them from the Earth. There’s more than enough oddness in the Australian fossil record for a whole book. But for now, we will end our exploration here.

Sources:

Koolasuchus: Last of the Giant Amphibians

Koolasuchus - The Antarctic Amphibian That Ate Dinosaurs

The last last labyrinthodonts? Warren et al (1997)

Researchers find a ‘fearsome dragon’ that soared over outback Queensland

New 'iron dragon' pterosaur found in Australia

Steropodon page on the Australian Museum

South Polar region of the Cretaceous- Wikipedia

Global Biogeography, by J.C. Briggs (1995)